Sustainability

There are growing concerns about the sustainability of growth in Pakistan, from rapidly declining water availability to growing inequalities across locations and income groups. Growth is most effective in raising income levels when it is environmentally sustainable, in that it uses resources to support growth today without compromising on growth in the future, and when it is socially sustainable, in that it ensures an inclusive growth pattern that allows all members of society to realize their economic potential for growth and benefit from it in return. Key risks to the sustainable use of resources include air and water pollution, rapidly declining water availability and the impact of disasters on fiscal outcomes. Key constraints to inclusiveness are increased inequality in outcomes and opportunities, and the emergence of inequality traps, as well as social norms that contribute to these outcomes. For Pakistan to sustain growth over the next 30 years, these concerns on environmental and social sustainability need to be addressed. This chapter first discusses briefly the key constraints to environmental and social sustainability, before going on to discuss, in turn, the type of reforms that would contribute toward a more sustainable development path.

PART 1: ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY

The main environmental sustainability challenges in Pakistan are: (i) managing air and water pollution; (ii) managing land and water sustainably (the agriculture and water nexus); and (iii) building resilience to natural disasters.

Air and Water Quality

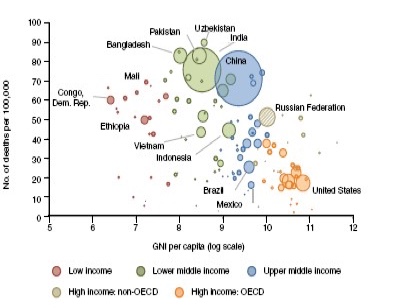

The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) ranks Pakistan 176 out of 180 countries in terms of air quality. Air quality measures, such as the concentration of fine particulate matter (PM 2.5), suggest that Lahore and Karachi both have worse air than Beijing, and that Pakistan’s concentration of PM 2.5 is very high compared with many countries at similar income levels (Figure 33). Pakistan’s economy is very airpollution intensive. In Pakistan, one unit of PM 2.5 generates US$18.9 of GDP per capita, while it is associated with US$145 of GDP per capita in China. Air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) are largely driven by the road transportation sector.

Increasing economic activity and rapid urbanization have put pressure on water availability and quality. The worst pollution of drinking water is seen in rapidly urbanizing and industrializing Pakistan. Surface water supplies are increasingly threatened by wastewater pollution. In 2013, only 5 percent of effluents were being collected and treated (World Bank, 2013b). Up to one-quarter of the population may be at risk from arsenic contamination of water. Industrial pollutants often contaminate water systems because treatments that control infectious agents are not effective in removing many toxic chemicals from drinking water. Sources of drinking water may be contaminated because of a lack of regulated municipal wastewater collection systems.

Access to water and sanitation has improved, but the quality remains low. On the EPI, Pakistan ranks 140 out of 180 countries in water and sanitation, with only 36 percent of the population having access to safely managed drinking water. Water utility services are intermittent, because of high leakage levels, limited supply, and insufficient access to power due to limited capacity or a lack of payment, with a very large difference in access between urban (96.9 percent) and rural (59.7 percent) areas. Nearly 20.2 percent of urban areas and 13.6 percent of rural areas have unsanitary drainage flowing directly into the nearby environment, with no sewer, septic tank, or pit. Pakistan’s income quintile differences in access rates to improved water and sanitation are higher than the international benchmarks (WHO and UNICEF, 2017).

Low air and water quality have profound impacts on human lives and economic growth. Air pollution, which affects growing urban centers the most, affects health and labor productivity, and detracts from the benefits of agglomeration economies. Air pollution is also linked directly to lower on-the-job productivity of workers (Chang et al., 2016). The inadequate quality of drinking water has increasing health and economic consequences for Pakistan. Poor water supply and sanitation contribute to high levels of childhood stunting undermining human capital. As of 2006, 20 to 40 percent of hospital beds were occupied by patients suffering from water-related diseases, such as typhoid, cholera, dysentery and hepatitis, which were responsible for one-third of deaths (World Bank, 2006). As of 2016, the annual cost of inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in Pakistan was estimated to be US$2.4 billion in urban areas (0.9 percent of GDP) and US$5.1 billion in rural areas (1.8 percent of GDP in 2016).

There is limited monitoring of environmental quality standards. The National Environmental Quality Standards (NEQS) are largely in line with World Health Organization (WHO) standards. However, these are not being properly monitored and evaluated due to institutional difficulties. The provincial environmental protection agencies (EPAs) have not assumed the operations and maintenance (O&M) costs of the air quality monitoring network that was developed by the central government. In mid-2012, the monitoring network suspended its operations because of the EPAs’ failure to cover their O&M costs. The regional authorities perform some monitoring of drinking water, but not on an annual basis. Overall, water resource management is compromised by poor water data, analysis and weak processes for water resources planning and allocation.

Managing Land and Water Sustainably: The Agriculture-Water Nexus

Water demand is projected to grow by at least 40 percent over the next 30 years. Recent analytical work suggests that demographic and economic growth are the largest drivers of demand increases across all sectors (World Bank, 2018a). In addition, climate change will see further increases in water demand (chiefly from agriculture) in the absence of attention to demand management. While agriculture continues to represent the bulk of demand, much of the demand increase will come from other sectors of the economy.

Between 16 and 32 percent of the increase in water demand by 2050 could be attributable to climate change, primarily because of higher water requirements in agriculture.

In the absence of effective demand management, growth in water demand will not be sustainable. Current withdrawal levels are already nearing 60 percent of renewable water supply, making a large increase in water demand unsustainable. Future surges in demand are unlikely to be manageable even through further unsustainable increases in groundwater pumping. The water-thirsty, low-productivity development model of the agriculture sector (see discussion below) is not sustainable. The demand management strategy needs to focus on efficiency improvements that can allow consumption to increase. Importantly, to accommodate growth in other sectors, food security, gains in value addition, and build resilience to ongoing climate change, it is critical for agriculture to improve water management, encourage water productivity and saving, and diversify crops toward higher value-added horticulture.

Agriculture, by far the largest user of water, uses it very inefficiently. Agriculture accounts for more than 90 percent of withdrawals and is heavily dependent on irrigation. More than 90 percent of agricultural production is concentrated on irrigated land (Yu et al., 2013). Though agriculture contributes around onefifth of national GDP, less than half of this is from irrigated cropping and the four major crops (wheat, rice, sugarcane and cotton) that represent nearly 80 percent of all water use generate less than 5 percent of GDP. Over the past 50 years, the agriculture sector’s growth rate has declined from an average 4.5 percent a year to 2.5 percent a year, led by a decline in productivity (Figure 34). Agriculture productivity is characterized by little technical change and instead the intensification of input use (Malik et al., 2016). Water use is wasteful, with governance issues that provide only weak incentives to save water. This results in overall low economic productivity (around US$1 per cubic meter, one of the lowest in the world) and concerns regarding environmental sustainability (for example, contamination and salinization of groundwater aquifers, which pose the greatest threat to long-term ground water sustainability in Pakistan).

Irrigation water is underpriced and the system badly managed. There is significant potential to improve water productivity in the agriculture sector, achieving higher efficiency and orienting water toward highervalue uses. Irrigation water tariffs (abiana) are set too low to cover the O&M costs of canal irrigation management and distribution systems. For example, they only cover 10 to 15 percent in Punjab. In addition, abiana are now charged (since FY04) on the basis of a flat rate per hectare, making farmers insensitive to water saving and efficiency. There are inadequacies in how areas are assessed for water tariffs and abiana collection is uneven, inefficient and inequitable. Irrigation service delivery by the public sector is generally poor, with concerns over the equity and reliability of water distribution. Farmers at the tail end of the canals invariably do not receive their share of water due to the poor physical state of the canals, water theft by farmers upstream and rent-seeking by operators.

Improved water management will need to be accompanied by improved agricultural policies. Despite reforms in the past, the state continues to intervene in agricultural markets, creating distortions that hold the sector back. The public sector intervenes through administered prices and protective trade policies. The support is concentrated in wheat (through domestic procurement, temporary import/export control, and subsidized sales to select flour mills) and sugarcane (through import tariffs, as well as support prices and export subsidies), while some support remains for dairy products and vegetable oils. In addition, input subsidies (on fertilizers, electricity for water pumping, or implicitly, on canal irrigation water) also influence farmers’ decisions. These interventions result in high fiscal costs, distorted cropping decisions and imbalanced input use, with implications for sustainability. The support is highly regressive, with most subsidies and benefits captured by large farmers and firms (Dorosh et al., 2016). For continued economic growth, agriculture must produce more from less, and reforming distortions in the agriculture sector will help move water toward higher-value crops.

Institutional and capacity issues have undermined water and environmental management in Pakistan, including weak environmental institutions, low financing, a lack of accountability and transparency, and limited intersectoral coordination. Addressing Pakistan’s water security calls for infrastructure development that requires significant financial resources, which are currently well below recommended levels. Devolution has further complicated the institutional set-up, causing coordination, funding and capacity difficulties. For instance, provincial water shares have been formally defined but these have been shown to be economically sub-optimal and there is insufficient clarity on risk-sharing during times of acute scarcity. The biggest challenges are of governance, both irrigation governance and urban water governance, and these are linked to inadequate legal frameworks, incomplete policies and inadequate implementation. Resistance to reform comes from deeply embedded vested interests in the status quo. Poor environmental management is already having a significant impact on productivity and growth by limiting the benefits of agglomeration economies, as discussed above.

Building Resilience to Natural Disasters and Climate Change

Climate change compounds environmental and development challenges. In the absence of adaptation, climate change will have profound implications for growth in Pakistan, leading to annual GDP losses of up to 1.2 percent by 2050 (Davies et al., 2016), and for poverty reduction, pushing between 5.7 and 21.4 million additional people into poverty by 2050. It is also the biggest longer-term and currently unmitigated external risk to Pakistan’s water security, and is expected to increase variability in water inflows between and within years. Climate change will affect agriculture adversely, with yields of staple crops projected to decrease up to 20 percent and livestock production predicted to decline by as much as 30 percent. A key dimension of vulnerability in Pakistan is exposure to hydrological and meteorological hazards, including floods and droughts. Pakistan is ranked seventh on the Global Climate Risk Index and climate change is expected to increase the occurrence and severity of extreme weather events, with high human and economic costs. The rapidly urbanizing cities of Pakistan are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat events owing to socioeconomic characteristics and unplanned development. One example is the 2015 heatwave in Karachi, which resulted in the deaths of more than 1,200 people over the course of a few days.

Poorer populations tend to be more exposed to disasters, suffering higher relative losses to their assets and livelihoods. Mostly a result of monsoon rains from July through September, Pakistan experiences frequent and severe flooding in the Indus River Basin, where millions live in low-lying areas. In addition to climate-induced disasters, Pakistan is periodically affected by geohazard disasters. Earthquakes occur frequently, with the 2005 earthquake causing over 70,000 deaths in the northern parts of the country.

The institutional set-up for disaster risk management is challenging. Pakistan improved regulations and institutional capacity for disaster management after the 2005 earthquake, including the National Disaster Management Act 2010. Following the passage of the 18th Constitutional Amendment in 2010, provincial disaster management authorities (PDMAs) have assumed an enlarged mandate and greater implementation responsibility to prepare for and respond to disasters. Several entities in addition to the National Disaster Management Authority are working on disaster risk management (DRM), with overlapping mandates at the federal level, including the Earthquake Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Authority, the Emergency Relief Cell, and the Federal Flood Commission, among others. This multiplicity of institutions at the provincial level includes the PDMAs, the provincial irrigation departments, and the civil defense and rescue services. The heavily decentralized approach to DRM in the provinces and a lack of standardization are key contributors to the challenging environment. In addition, the post-disaster financial responsibilities of provincial governments are not well-defined.

Securing access to financial resources before a disaster strikes is important. Natural disasters generate significant fiscal risk and create significant budget volatility. The NDM Act 2010 allows for the establishment of disaster management reserve funds at the national and provincial levels. Annual budgetary allocations, mandated in the NDM Act 2010 are made in an ad hoc manner and often used for response activities, and are not channeled toward risk mitigation. Other recent initiatives that need follow-up include the establishment of the National Disaster Risk Management Fund and the development of agri-insurance for farmers, to protect them against disasters and climate risks.

PART 2: SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY

A sustainable development path involves creating an inclusive society, not only in terms of economic welfare but also in terms of the voice and empowerment of all groups (World Bank, 2013a). Social inclusion matters by itself, not only because it allows people to contribute to and benefit from growth, but also because social exclusion is costly. Equity is an enabling factor for growth and social exclusion means that selected groups will not contribute their labor and capital to production processes, which can lead to lower production and productivity (e.g., see de Laat, 2010, for a discussion of the economic impact of Roma exclusion in several European countries). For example, low female labor force participation robs a country of the contribution of a large share of its population. Social exclusion is about the waste of valuable human capital when people are not able to fulfill their potential. Inclusion is therefore important as Pakistan seeks to accelerate and sustain growth over the next 30 years. The key constraints to social inclusion include increasing inequality in outcomes and opportunities, as well as limited mobility.

Poverty and Inequality

Persisting inequality is undermining Pakistan’s ability to make the best use of its labor force and sustain growth over a long period of time. Inequalities across and within regions persist, and there are signs that prosperity is not being shared by the poorest segments of the population. More worryingly, the existence of inequality traps—in which exclusion is transmitted across generations—and inequality of opportunities across space and between genders, suggest a deficit of equity in the process of socioeconomic development. If left unattended, this could harm both growth and social stability in the long run.

The relationship between growth and poverty reduction has been different across periods. During the 1960s, economic growth had an ambiguous impact on poverty because of rising poverty and widening inequalities. Policy changes during the 1970s dampened growth, but despite lower growth the perception was that welfare of the poorest improved. In the 1980s, improved economic policies and favorable external factors, such as opportunities for migration in the Middle East, led to an uptick in growth, which averaged 6 percent annually, and a substantial decline in poverty. The trend reversed during the 1990s and poverty remained almost unchanged between 1991 and 1999. The period between 2001 and 2015 was characterized by an uninterrupted and significant decline in poverty, from 64.3 percent in 2001 to 24.3 percent in 2015. Drivers of this reduction include economic growth, an increase in international migration, and the expansion of social protection, along with urbanization and growth of the (informal) off-farm economy.

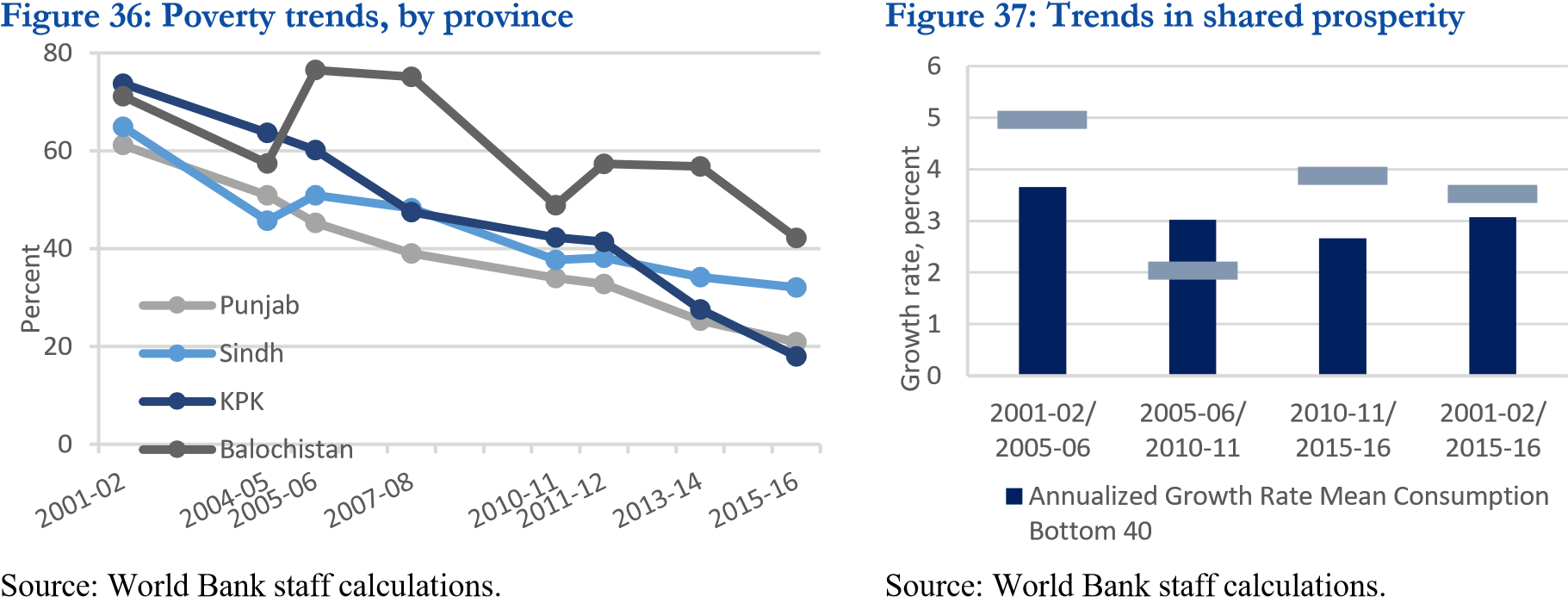

However, the pace of poverty reduction was not uniform throughout Pakistan. Between 2001 and 2015, poverty in urban areas declined at an annualized rate of 9 percent, compared with 6 percent in rural areas. A substantial stagnation in the urban/rural profile was matched by a general trend in poverty convergence at the provincial level (Figure 36). Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Punjab were particularly successful at continuously reducing poverty between 2001 and 2015. While Sindh halved poverty over the period, progress was slower in Balochistan. The equalizing trend also occurred within provinces, as poorer districts experienced a larger reduction in poverty. Urban-rural inequalities remain prominent also within provinces. With the unique exception of KP, the poverty gap between urban and rural areas increased in all provinces, most notably in Sindh and Balochistan.

Analyzing shared prosperity trends (measured as the average consumption of the poorest 40 percent) suggests increased inequality. As shown in Figure 37, except for the period between 2005 and 2010, consumption growth was stronger at the higher end of the income distribution. Average consumption growth of the bottom 40 percent decelerated progressively, from 3.7 percent annually between 2001 and 2005, to 3 percent between 2005 and 2010, and to just 2.2 percent between 2010 and 2013. Between 2010 and 2015, not only did consumption of the poorest 40 percent grow less than previously recorded, but it also grew 1 percentage point less than the average of the population, resulting in an increase in inequality. Consumption inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient increased only marginally, from 27.5 in FY02 to 30.3 in FY16. However, this inequality index is calculated using Pakistan’s Household Integrated Economic Survey. Similar to many other household surveys, this survey may be missing many households at the upper end of the income distribution, significantly underestimating inequality (see Pakistan@100 policy note ‘From Poverty to Equity’ for a detailed discussion on this issue).

Economic and Social Mobility

Actual and perceived inequality are amplified in societies that lack socioeconomic mobility. Inequality and intergenerational socioeconomic mobility are closely intertwined. From an intergenerational perspective, when children can aspire to achieve levels of education, jobs and living standards that are materially better than the levels enjoyed by their parents, inequality can begin to decline over time. On the other hand, when the capacity to climb the social ladder is pre-determined by the lottery of birth, inequality persists over time, with negative consequences for equity and dynamic efficiency. A society that lacks mobility is unable to mobilize all available talents, leading to lower and less inclusive growth,

Pakistan has one of the lowest rates of intergenerational mobility in the world. A recent report (World Bank, 2018b) analyzing trends in intergenerational mobility in education across 146 countries indicates that Pakistan ranks among the lowest performing countries in educational mobility. Another study provides additional evidence of limited mobility and inequality traps in rural Pakistan (Mansuri and Shrestha, 2018). The analysis corroborates the low level of education mobility across generations in Pakistan. A key driver behind this is land inequality: poor households residing in villages where land is less equally distributed are less likely to have escaped poverty over time. Similarly, upward education mobility is significantly lower in villages where land distribution is more concentrated. The accumulation of assets by households differs significantly between those villages with the most equal land distribution and those with the most unequal land distribution, with poorer households being more likely to accumulate livestock in villages with a lower level of land inequality.

Inequality of Opportunities

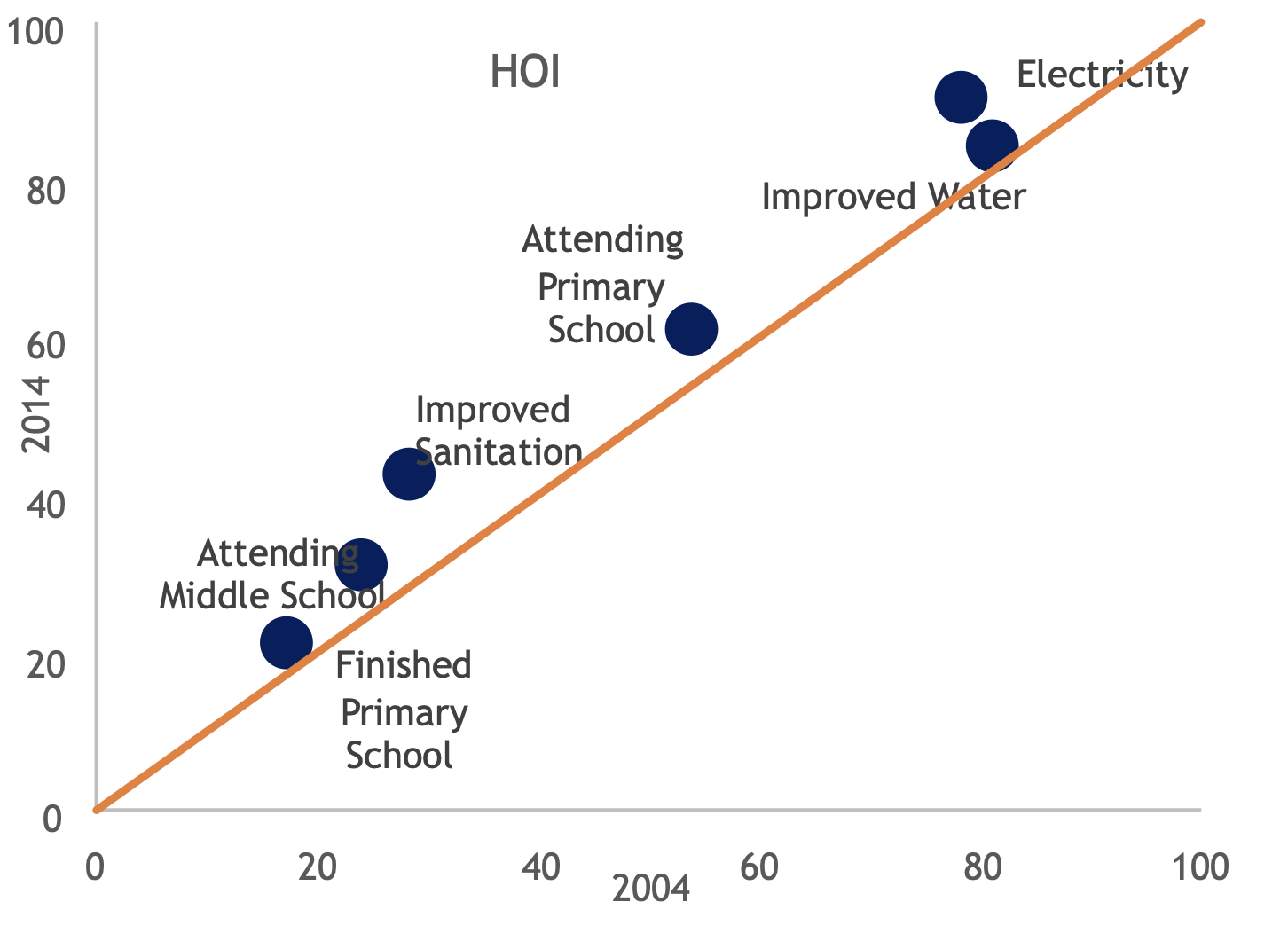

Basic opportunities, such as completing primary school on time, or having clean water to drink, appear to be far from universal and are unevenly distributed across Pakistan. Understanding the extent to which circumstances at birth affect opportunities and whether the “opportunity gap” is improving over time is important in promoting justice and avoiding wasted human potential. The Human Opportunity Index (HOI) was developed to capture the extent to which opportunities are evenly distributed within a society (see the Pakistan@100 policy note ‘From Poverty to Equity’ for a detailed discussion of the HOI). Opportunities for children are defined as access to a set of basic goods and services in education, health and infrastructure that are deemed necessary to realize human potential later in life. As can be seen in Figure 38, access to basic opportunities is far from universal. Analysis suggests that not only access to services, but also the quality of those services is unequally distributed. Equally worrisome, progress over time in the HOI has been marginal. If the overall objective is not only to widen coverage, but also to promote the equality of basic opportunities for children, public policy should be oriented toward directing marginal investments to increase basic opportunities for the most disadvantaged groups. Figure 38: HOI trends, national level, 2004-14

Source: World Bank staff calculations nased on PSLM 2006 and 2014.

Source: World Bank staff calculations nased on PSLM 2006 and 2014.

A household head’s education and location are the most important circumstances that determine inequality in access to education and infrastructure services. Differences in where children are born (province and urban/rural location) are more relevant for inequality of opportunities in basic infrastructure, while the education of the household head is the most relevant circumstance for inequality in education opportunities. HOI analysis reinforces evidence of sharp inequalities across provinces. Inequality of opportunities is highest in Sindh and Balochistan. In Punjab and Sindh, the education of the household head is the most significant determinant of access to educational opportunities. In contrast, gender is by far the most important in KP and Balochistan, where social norms penalize girls’ education the most.

Aspiration Gaps and Intergenerational Transmission of Gender Inequality

Existing inequalities can lower the aspirations of individuals in disadvantaged groups and contribute to the transmission of disadvantages across generations. Aspirations interact with social hierarchies and norms, reinforcing their impact on outcomes and reproducing them over time. For example, high gender inequality can lead to the waste of human capital through lower aspirations for and from girls, resulting in significant losses in terms of both GDP and wealth.

In Pakistan, the interplay between aspirations and social norms in perpetuating disadvantages over time is particularly evident in the context of gender inequalities. Pakistan ranks 143 out of 144 countries on the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index. Female literacy is as low as 48 percent, 25 percentage points lower than male literacy. Female labor force participation, while it almost doubled from 13.3 percent in 1992 to 26.3 percent in 2017, remains one of the lowest, not just in South Asia, but globally. Underlying these statistics is the rigidity of the form of patriarchy that women and men experience in Pakistan. This system provides incentives to devalue women and girls, whose agency is thereby severely limited (Solotaroff and Pande, 2014).

Parents have greater aspirations for their sons than their daughters. Patriarchal social norms create and perpetuate gender inequality, also in aspirations for the future. A recent study (Gine and Mansuri, 2018) compares the aspirations of parents for their sons and daughters in terms of education and employment with the aspirations of these boys and girls. Both mothers and fathers had greater aspirations for their sons (Table 3), and this gap was confirmed by the aspirations of boys and girls for themselves (Table 4). Girls aspire to have less education than boys, but nonetheless higher than their parents’ expectations. The desire to work is nearly universal among boys, but only half of the girls express a desire to work, in line with their parents’ aspirations. Parents’ and adolescents’ aspirations are closely tied to individual and household characteristics, such as poverty and education. Mothers and fathers with some education desire significantly more education for their children, but they still have higher aspirations for the education of boys.

Table 3: Parents’ aspirations for children

| Mothers' aspiration for: | Father's aspirations for: | |||

| Daughters | Sons | Daughters | Sons | |

| Preferred years of education | 7.28 | 10.15 | 8.51 | 11.74 |

| Expected age at marriage | 21.05 | 23.70 | 20.64 | 23.322 |

| Child will have some say in choice of spouse (%) | 13.10 | 51-30 | 2.69 | 40.00 |

| Preferred number of children | 4.37 | 4.75 | 3.75 | 4.05 |

| Prefer more male children (%) | 20.50 | 34.50 | 31.40 | 35.50 |

| Allowed to work (%) | 50.50 | 97.30 | 56.40 | 99.40 |

| Allowed to work for NGO (%) | 33.50 | 89.20 | 35.80 | 92.80 |

| Allowed to contest local elections as candidates (%) | 29.60 | 81.90 | 22.40 | 67.10 |

Table 4: Adolescents’ own aspirations

| Female | Male | |

| Preferred years of education | 9.16 | 10.98 |

| Child's preferred age of marriage | 22.17 | 22.83 |

| Will choose spouse themselves (%) | 4.70 | 20.00 |

| Preferred number of children | 3.46 | 4.25 |

| Prefer more male children (%) | 17.00 | 34.30 |

| Wants to work (before marriage) (%) | 51.90 | 97.90 |

| Wants to work (after marriage) (%) | 47.20 | 97.10 |

| Wants to work for NGO (%) | 26.40 | 84.30 |

| Would like to run for elections (%) | 11.30 | 60.00 |

Poverty and Conflict in Pakistan

Persistent inequality among and between socioeconomic groups may increase social discontent and, eventually, the propensity of individuals and groups to engage in crime and political violence. Relative deprivation and the exclusion of segments of society from sharing in the benefits of economic progress can fuel discontent and create a fertile ground for conflict to flourish. Between 2001 and 2011, conflict claimed the lives of 35,000 people in Pakistan. According to government estimates, the direct and indirect cost incurred by Pakistan due to incidents of terrorism during the past 16 years amounted to US$123 billion.14 Recent research in Pakistan suggests that poverty, inequality, and a weakening social contract between citizens and the state can contribute to radicalization and militancy (Zaidi, 2010; Azam and Aftab, 2009; Malik, 2009). The relationship between deprivation and conflict is complex, as other research suggests, showing a limited correlation between education levels or employment with militancy (Abbas, 2007; Fair, 2007; Fair, 2008; Bullock et al., 2011). The government, in its recently approved National

Internal Security Policy, reflects the complexity of the security challenge and envisions a “peaceful, democratic and inclusive society forged by the promotion of the rule of law, inclusive growth, political stability, and respect for diversity.” Increasing regional inequalities, competition for scarce natural resources (most notably water), and the compounding effect of climate change are likely to exert further stress on Pakistani society’s resilience to conflict and violence.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Ensuring environmental and social sustainability is key to sustaining growth, as it prevents a depletion of the natural resource base and enhances human capital by ensuring that everyone can participate in and contribute to growth. The priority reform for sustainability is improved water management, particularly in the agriculture sector. Ultimately this will require that water prices reflect their scarcity value and the true costs of delivering this crucial service, but a number of institutional and legal reforms may be necessary first to strengthen the capacity of concerned institutions. This section outlines the general direction that reforms focusing on improving the sustainability of growth should take. For a more detailed discussion of the suggested reforms please refer to the Pakistan@100 policy notes ‘Environmental Sustainability’ and ‘From Poverty to Equity’.

Environmental Sustainability

Recommendations to improve environmental sustainability can be grouped in four different areas: (i) improving information (including measurement and monitoring) for decision-making; (ii) investing in water services delivery infrastructure to reduce water losses and pollution; (iii) getting prices right, given that significant externalities are not captured by market mechanisms; and (iv) developing risk-management policies. Improvements to institutional mechanisms related to coordination and decentralization are also important and discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

a. Improving information for decision-making

Improving the measurement and monitoring of air and water quality. A country cannot manage what it does not measure, and improving monitoring is crucial. Pakistan needs to improve its overall environmental monitoring. Monitoring of water and air quality is instrumental for planning, implementation and evaluation, but it is difficult to do at the current low capacity levels. To improve capacity, the authorities will need to invest in equipment, human resources and the institutional set-up. Monitoring will require the coordination of operators, and local and provincial authorities, with oversight by the federal environmental authority. Monitoring would benefit from partnerships with research centers, academic networks and universities, as well as the use of modern technologies.

Improving water measurement and accounting to manage the water supply. This can be done by tracking and improving water productivity, enhancing trust and ensuring equity among water users (be it among provinces or among sectors). Monitoring should go beyond water availability in irrigation canals and surface water bodies, since there are vast domains in Pakistan’s water resources, such as the cryosphere or groundwater aquifers, that are still poorly understood and managed. Enhanced hydrometeorological monitoring and use of Earth Observations can provide a better understanding of natural and induced water losses and, together with other traditional models, can guide improved water resource planning, and improved flood risk assessment and forecasting. Groundwater monitoring is urgently needed to manage this resource’s sustainably, including its quality and pollution levels. In addition, water data need to be openly shared among all stakeholders to build trust between water users and water managers.

Introducing a risk-management system that helps safeguard farmers from the adverse impacts of weather hazards on crops and livestock. The system would aim to reduce livestock and crop losses in climate vulnerable areas, and build the resilience of farmers by providing them with coping mechanisms and strategies to deal with climate shocks. It would include improved Climate Information Services (CIS) that farmers can use to inform their decisions, as well as developing climate indices to trigger early warning and response, or (parametric) insurance.

Pakistan can reduce disaster losses through improved urban planning, incorporating risk considerations into the decision-making process and investing in risk reduction. Risk identification and the integration of risk information in land use and territorial development, urban planning, and the design of public infrastructure, as well as the adoption and monitoring of better building standards, are effective ways of reducing risk. Once disaster risks have been identified, they must be communicated to motivate users of that information to increase resilience to disasters. Pakistan should also raise awareness of risks and risk-mitigation principles, since awareness leads to public demand for risk-resilient policies. b. Investing in water services delivery

b. Investing in water services delivery

Modernize existing irrigation networks to reduce water-logging and salinity. The low quality of irrigation services across Pakistan restricts improvements in water productivity. There is a need to systematically improve drainage infrastructure, rehabilitate canals and distributaries, and install improved hydraulic control structures with flow monitoring and automation systems. In addition, water allocation processes should be updated to increase transparency and equity, giving farmers greater clarity on their water supply. Given the scale and complexity of surface water irrigation in the Indus River Basin, this modernization and its associated reforms will need to be implemented gradually.

Reform urban water service delivery to meet the growing demand. Urban water service delivery in Pakistan has not kept pace with urbanization and the quality of water in urban areas is rapidly declining. There is a need for major infrastructure investments, particularly in wastewater treatment along with improved operations and maintenance of bulk water delivery systems and sewerage networks. In the short term, the government should develop and disseminate standards for urban water delivery and link service tariff increases to service quality. Stronger coordination should be established between public land-owning and service-delivery agencies to link service delivery to urban planning. An enabling environment should also be created to involve private sector operators in infrastructure and service provision.

Address the infrastructure and financing gap in rural sanitation services. Rural sanitation services in Pakistan are inadequate and suffer from infrastructure gaps, inadequate financing and an absence of reliable revenue streams to cover O&M costs. There is a need to strengthen the capacity and increase financing of provincial government departments responsible for rural sanitation. Investments are required in infrastructure for sanitation services, including wastewater collection, and basic treatment and disposal at the village level. The government should establish mechanisms to ensure a sustainable revenue base required to cover O&M costs. In addition to infrastructure and finance, however, improving rural sanitation will require increased public awareness and behavior change among rural communities.

c. Pricing environmental costs correctly

Pricing environmental costs correctly so that economic actors internalize those costs. Pakistan needs massive and increased investments for growth, so ‘greening’ investments is critical. Economic actors respond to pricing. Regulatory approaches must therefore be complemented by interventions that ensure economic actors internalize environmental costs, including a greener tax regime (e.g., carbon taxes) and the elimination of environment-damaging subsidies (removal of subsidies for fuels consumed by motor vehicles and industries). The legislative gaps of the Pakistan Environmental Protection Act (PEPA) regarding the implementation of environmental taxes should be addressed. The ‘polluter pays’ principle will need to be sustained through secondary legislation and a mechanism to ensure that polluters are the ones that cover the environmental costs.

Water pricing is an important tool to encourage efficient water use. Currently, the abiana rates do not even cover the O&M costs of the surface irrigation network, let alone the externalities associated with the extraction of groundwater and its environmental impact. Effective abiana rates could help incentivize a more efficient use of water in agricultural systems and contribute to mobilizing sufficient funds to address the underinvestment in the irrigation network. Beyond a service fee, which covers the costs of providing the irrigation service, there could be consumptive use charges to incentivize judicious water use. Increased abiana rates would need to be complemented by other well-designed policies to tackle various market and government failures, including supporting awareness-raising and capacity building, and investing in relevant R&D initiatives, and fostering demand and supply for water-efficient technologies and practices.

Improvements are required in assessing the areas for abiana rates, in setting differential tariffs that reflect the level of services provided, and in the efficiency and completeness of tariff collection. These should include an improvement to the local irrigation departments’ abiana assessment procedures, and an improvement in recovery rates. The involvement of water users in irrigation management would help to improve management, although it will be important to ensure that the interests of small farmers are also represented. In the longer term, the introduction of volumetric water pricing should be considered, making use of progress in remote-sensing technologies. This would be a second-generation reform, given the necessary preparatory work and the difficulties in implementation.

Reforming agricultural policies that distort input and output prices. Pakistan continues to support a number of crops through subsidies, trade restrictions and marketing practices. The value of agricultural subsidies is many times larger than the public resources allocated to productive investments for agriculture. Most subsidies are of a regressive nature and generate negative environmental externalities. They are mostly focused on major crops rather than higher value-added agriculture. These policies often serve vested interests, making their reform politically sensitive (good examples include the public wheat procurement program, electricity subsidies for tube wells and low abiana rates). Pakistan needs a new policy orientation with measures that reduce subsidies and protection for certain sectors, while strengthening the provision of public services. The implementation of these reforms is expected to result in significant fiscal savings and social benefits (through lower prices to consumers). These reforms also need to be accompanied by targeted support to poor farmers to help them cope with any adjustment costs.

d. Developing risk-management instruments

Develop Disaster Risk Financing (DRF) mechanisms to help the government cope with the financial impact of disasters. Pakistan needs a comprehensive framework of risk-financing instruments to improve early and comprehensive responses to disasters. A DRF strategy would enable the government to make an informed choice on accessing various sources of funding to respond to disasters, using a mix of financial instruments to protect Pakistan against disasters of different frequency and severity (including reserve funds, risk-transfer mechanisms, contingent credit and cash-transfer mechanisms).

Due to rapid urbanization and unplanned construction, coupled with inadequate management of infrastructure, the vulnerability of the population has grown over past decades. The underlying risk needs to be mitigated by strengthening infrastructure and promoting safe construction practices. The government needs to identify a priority list of critical infrastructure that requires retrofitting to reduce structural risk. The current regulatory environment governing the construction sector in Pakistan is opaque and the enforcement mechanisms for urban development control do not address structural safety. There is a need to periodically update the building code and also ensure its enforcement to mitigate structural risk.

Social Sustainability

Prosperity is not being shared equally among the population. A sizeable portion of Pakistan’s immense human capital potential is being wasted due to the lack of economic mobility, inequality of opportunities and aspiration gaps. Breaking inequality traps requires stronger efforts to reduce spatial inequalities, and target lagging areas and marginalized segments of the population. Bringing Pakistan along the path to a more inclusive development process requires a comprehensive strategy of interventions aimed at equalizing opportunities and tackling social norms that facilitate social exclusion.

Reducing spatial inequalities will require improving mechanisms that form the basis of intergovernmental transfers—federal/province/district. This could entail making development gaps more explicit in the allocation formula used for the National Finance Commission (NFC) award of federal divisible pool transfers to provinces and improving accountability by providing adequate incentives for performance. Similarly, development gaps and performance could also be formally introduced in the allocation of resources from provinces to districts. Reforms aimed at anchoring resource allocation to local development needs should be complemented by efforts to address capacity and accountability constraints at the local level. The authorities could also tailor modes of service delivery to the specific needs of communities in lagging areas by, for example, combining interventions aimed at addressing quantity and quality constraints on the supply side (building/improving facilities, training teachers or health workers) with others addressing constraints on the demand side (conditional cash transfers, outreach campaigns).

Introduce legislative interventions to strengthen protection against discrimination and gender-based violence. Tackling social inequalities will require challenging existing power structures and social norms on which exclusion and inequalities based on gender, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation or other group characteristics are grounded and transmitted from one generation to the next. In addition to legislative action, greater participation of women and minority groups in politics and the economy should be promoted through affirmative action. Programs aimed at promoting an equitable and inclusive evolution of social norms, such as school-based programs to strengthen the life skills of adolescent girls, the provision of safe spaces for girls, and access to peer networks could promote more gender-equitable attitudes and support female empowerment. Programs engaging young men and boys through group education sessions, positive role models of masculinity, and mass-media campaigns have also shown encouraging results in reducing partner violence and support for inequitable gender norms.

Policies and programs aimed at fighting poverty and equalizing opportunities should be designed to include the poorest segments of the population. These interventions should go hand in hand with strengthening access and quality of service delivery in lagging areas. Potential interventions include: (i) conditional cash transfers to support school enrolment, maternal health and early childhood nutrition programs; (ii) awareness campaigns to strengthen accountability in service delivery and support human capital investments; and (iii) labor market interventions to support employability and income generation (training on soft skills, training in literacy, placement services, etc.). Social protection programs such as BISP can be built upon for climate-smart targeting, reaching out to vulnerable households and for disaster relief responses. Improved targeting of assistance programs for the poor and vulnerable would also contribute to more effective policies.