Allocation

Countries achieve higher productivity through more efficient resource allocation. Nearly 75 percent of the GDP per capita gap between Pakistan and the United States is explained by the gap in total factor productivity (TFP). In line with other countries, productivity differences explain, on average, 70 percent of the difference in income levels (Jones, 2015). Misallocation of capital (both human and physical) across sectors, across firms, and within firms, results in productivity differences. Structural transformation is about how resources can be reallocated to more productive use. Reallocation of resources can also happen between the tradeable and non-tradeable sectors, important for Pakistan given the economy’s reliance on the domestic sector. For most countries structural transformation has meant the relative decline of agriculture, as resources have moved toward higher-value activities in manufacturing and services, contributing to raising aggregate productivity. The shift from farm to non-farm activities is often facilitated by rising agricultural productivity and the emergence of labor-saving technologies, which frees up resources for other sectors.

This chapter discusses structural transformation in Pakistan and identifies constraints to structural transformation and how these can be addressed.This chapter begins with a discussion on how structural transformation has evolved in Pakistan and then identifies three main constraints that have hindered Pakistan’s progress: (i) government failures; (ii) ineffective policies to address market failures; and (iii) the absence of regional integration. This is followed by recommendations and appropriate policy responses for each of the key constraint areas discussed.

Stylized Facts on Structural Transformation

tructural transformation in Pakistan has been slowing and seems to have stalled in recent years. Up to the early 1990s, Pakistan had been following the same path as many countries and its agriculture sector was declining as the country became richer. But this trend has slowed down over the past few decades. The slow decline in agriculture has not been accompanied by an increasing share in manufacturing and, as a result, today the manufacturing sector is small compared with countries at similar income levels (see Box 2 for a discussion on whether the path of focusing on labor-intensive manufacturing for exports is a possibility for Pakistan). Pakistan’s services sector is relatively large compared with countries at similar income levels and this divergence has increased substantially in recent years. However, most services sector growth has been in low-skills services (wholesale and retail trade) and public administration. Similar trends are reflected in the sectoral employment shares (Figure 21).

Pakistan’s agricultural productivity has not improved much over the past 30 years. The agriculture sector’s growth rate has progressively declined. Productivity growth is constrained as the sector is characterized by an inefficient crop mix and the over-use of resources such as water. As a result, growth has been driven by input increases rather than technical change (Malik et al., 2016). The mixed performance of agriculture has slowed structural transformation, as the sector’s share of the economy has declined far more slowly than in peer countries (Figure 22).

In addition to a constant agricultural share, Pakistan’s economy is characterized by a large informal sector that is retreating only gradually. Estimates for the size of Pakistan’s informal economy vary but suggest that between 25 and 35 percent of total economic activity is undocumented and untaxed. The size of the informal economy appears to have remained comparatively constant in recent years. For instance, the average of estimates in two recent studies suggest that the share of the informal economy only declined from 36 to 30 percent between 1982 and 2008 (Gulzar, Junaid and Haider, 2010), or even remained constant at about 25 percent over the same period (Arby, Malik and Hanif, 2010). While a large informal economy is a constraint to structural transformation and growth, evidence from multiple countries suggests that it can also act as a buffer that generates employment when the formal economy contracts (e.g., Loayza and Rigolini, 2006; World Bank, 2014).

There is potential to improve productivity through the reallocation of resources from less to more productive firms. Reallocation between sectors is not the only way that economies transform, and withinsector reallocation—to more productive firms and uses—is often just as important. A high degree of dispersion in productivity levels across firms in the same sector suggests that there is considerable room to improve productivity by facilitating resource reallocation to more productive firms. Comparison of productivity in the garment sector in Pakistan and Bangladesh suggests that the top Pakistani firms make significantly more output with the same inputs than their Bangladeshi counterparts, but there are large productivity differences in Pakistan, lowering average productivity. Comparison of productivity dispersion in Punjab with China, India and the United States shows much larger dispersion in Punjab. This suggests that reallocating resources from unproductive to more productive firms in the same sector has the potential to increase output, and thus economic growth.

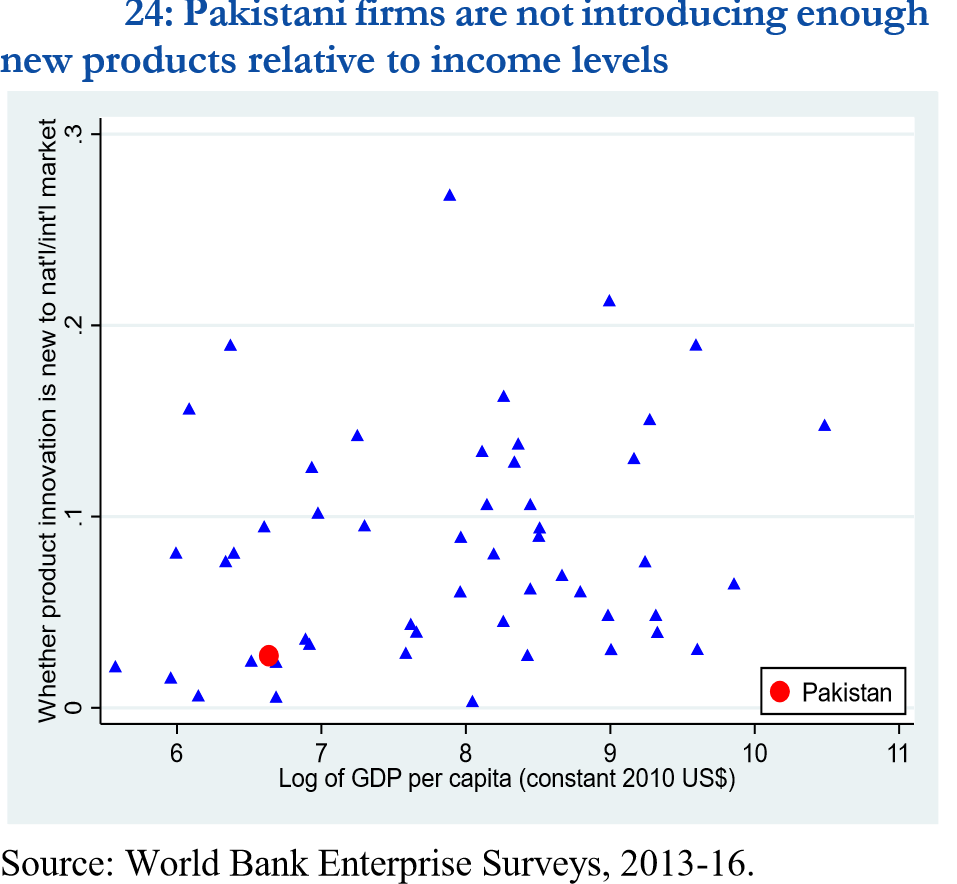

Structural change can also occur through improvements within firms, but the evidence suggests that Pakistani firms do not seem to be innovating much. Besides the allocation of resources to more productive sectors and firms, structural change can also occur through improvements within existing firms. In general, the rate of innovation in most Pakistani firms is relatively low, as reflected in the low percentage of firms that have introduced a new product in the past 3 years (Figure 24). However, there are some notable examples of firm dynamism. The Sialkot leather goods cluster of about 130 firms, mostly small-sized, is the world leader in the production of hand-stitched soccer balls and in recent years has entered new fields such as surgical instruments. In the textile sector, the cluster run by Faisalabad Industrial Estate Development and Management Company has made good progress. In major cities such as Lahore and Karachi, there are emerging ICT clusters involved in business-process outsourcing and software-enabled services.

Pakistan’s rapid urbanization can support efforts to transform the economy. In many countries, cities have become hubs for economic transformation through agglomeration benefits. People and firms benefit from being concentrated in a smaller geographical space, and structural transformation into higher valueadded manufacturing and services goes hand in hand with urbanization. Pakistan is the most urbanized large country in South Asia, with 36 percent of the population living in urban areas and urban centers account for over half of Pakistan’s GDP. The pronounced youth bulge, coupled with continuing rural-urban migration, provides a large labor pool. While until the late 1990s much migration was destined for Karachi, the past 20 years have seen significant migration from smaller cities to larger cities in Sindh, KP and Punjab. Some urban centers are showing emerging signs of functional specialization. For instance, manufacturing, finance and high-tech sectors are mainly concentrated in larger cities whereas construction, mining and agriculture-related sectors are more prevalent in smaller cities. However, Pakistan is not leveraging its cities optimally and transformation seems significantly slower than in other countries with similar urbanization and spatial agglomerations. While the concentration of economic activities in urban areas brings considerable benefits, it can also create congestion costs (traffic, pollution, price increases and crime) that can at times outweigh the benefits of agglomeration, negatively affecting productivity and growth. Whether the agglomeration benefits outweigh the congestion costs will depend on interventions to maximize the benefits, and to manage and mitigate the costs.

Digital development holds great promise as a driver of structural transformation. Increasing digitization, and particularly the proliferation of the internet, supports structural transformation through two channels. First, the internet is creating new types of jobs, work arrangements and opportunities for entrepreneurship, as it cuts search costs and market entry barriers, and makes it easier for workers, employers and customers to find each other, irrespective of their locations. Digitally enabled work can be inclusive, as services including delivery, ride-sharing, or housework tend to employ informal workers in urban and suburban areas of the country, and flexible work arrangements can encourage greater female labor force participation. Second, modern technology can enhance productivity in traditional sectors, and thus trigger structural transformation. In agriculture, for instance, digital technologies can overcome information barriers and open market access for many smallholder farmers, increase technical capacity through new ways of providing extension services, and improve agriculture supply chain management.

Pakistan has already derived some of the benefits from digitization, but scope for further growth remains. Demand for access to the internet has increased rapidly, from 6 million internet subscribers in 2013 to an estimated 48 million in 2017 (Pakistan Telecommunication Authority). Pakistan today is already the third-largest country providing workers to global online freelancing platforms, generating an estimated US$1 billion in export revenue in 2016 (Oxford Internet Institute). Pakistan is also an increasingly attractive “knowledge process outsourcing/business process outsourcing” destination, and the federal and provincial governments in Punjab and KP are actively supporting entrepreneurship through incubation programs. However, broadband and mobile penetration (basic and data/internet-enabled mobile phones) in Pakistan remains relatively low. Relative to its neighbors, the country also ranks low on most of the key enablers of a digital economy: infrastructure, affordability, consumer readiness and content. Crucially, there remains scope for improvement with respect to the inclusiveness of digitally driven growth: improvements to employment have been concentrated among the relatively fewer higher-skilled workers in the country, and the digital divide between men and women in Pakistan is among the highest in the world.

Box 2: Will the path of labor-intensive export industries be available to Pakistan?

Many countries in East Asia took advantage of low labor costs to develop labor-intensive manufacturing export industries. Countries seek to emulate this experience as a way of quickly transforming their economies. With labor costs quickly rising in China, many firms (both Chinese and foreign) may seek to relocate plants to third countries. Pakistan could attract some of those relocating plants. It is relatively close to China, has low labor costs and a large labor force. Many argue that the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) could also help in this process. But technological advances may mean that many manufacturing jobs will disappear in the medium term, reducing the possibilities of following a transformation path similar to that of East Asian countries in the past.

New technologies are transforming production processes by reducing the importance of low wages in determining competitiveness. These technologies are robotics (particularly artificial intelligence, or AI), digitalization and internetbased systems integration, including sensor-using “smart factories” and 3-D printing. These labor-saving technologies, which are among the most emphasized in the Industry 4.0 literature (Cirera et al., 2017), could significantly shift which locations are attractive for production, thereby challenging established patterns of comparative advantage. While not all these technologies are new, cost innovation, software advances and evolving business formats and consumer preferences are fueling their adoption.

How can a country such as Pakistan position itself given these developments? There is considerable uncertainty about the future. Concerns about the negative impact of technology on jobs have been around for centuries, but so far they have not materialized, although technology can disrupt labor markets by making certain jobs obsolete. Pakistan should position itself taking this uncertainty and the limited knowledge available about future job markets into account. In all likelihood jobs will look very different in the future, many current jobs will disappear and new jobs will emerge— similar to the experience of the past 40 to 50 years. There is increasingly a premium on adaptability, strong cognitive skills and less demand for routine tasks. Given this, Pakistan should invest in its main asset, its labor force, to ensure it has the necessary skills and capabilities to adapt to a more volatile, uncertain, and competitive job environment.

Constraints to Structural Transformation

a. Government failures

A key constraint to structural transformation is the persistence of market distortions, resulting from government failures. Government intervention can introduce market distortions that prevent resources from being allocated to the most productive uses. Opacity and arbitrariness in regulatory policies, subsidies and other market interventions that distort prices, can lead to the misallocation of resources across firms, and reduce their incentives to invest. A distortionary tax system provides strong incentives for firms to remain in the informal sector and thus delays structural transformation. Political favoritism generates an uneven playing field that allows unproductive firms to survive longer than if they were in competitive environments. Ineffective governance of key economic sectors, especially the financial and energy sectors, can reduce productivity by depriving firms in other sectors of crucial inputs. Pakistan’s economic policies have often been designed by a small elite such that the market is rigged in its favor (Hussain, 1999), leading to inefficient outcomes. This section discusses several areas of government failure that lead to resource misallocations, namely regulatory complexity, credit allocation, SOEs and power sector reform. Agricultural policies can also affect the allocation of resources, and this is discussed in the following chapter.

Regulatory complexity and inconsistency persist in Pakistan. Different rankings that measure regulatory quality or the business environment suggest that Pakistan is lagging behind most of its peers (Figure 25). Overlapping jurisdictions, and multiplying regulatory and tax requirements, make it difficult for firms to conduct business, affecting investment. For example, the regulatory regime in the manufacturing sector is administered by numerous national and sub-national agencies and departments through a wide range of age-old approvals, no objection certificates, permits and licenses. Textile firms pay as many as 12 different taxes, and deal with 47 different departments for various approvals and provisions (PIDE, 2018). Pakistan’s regulatory regime suffers from a perception among firms that it is unpredictably and inconsistently implemented, partly because the rules leave room for discretionary actions by government agencies. The costs associated with this regulatory environment affect firms’ investment decisions and the sectors they choose to invest in, which can result in resource misallocation.

Regulatory bottlenecks have also hampered ICT sector development and subsequently digital development. The main regulatory constraint to an otherwise competitive telecoms market relates to the issuance of mobile internet licenses. Delays in the issuance of 3G and 4G licenses, which was eventually completed in 2014, had prevented telecom companies from building out and upgrading their networks to carry data services. Going forward, similar delays in the deployment of 5G networks would delay a revolutionary leap in capacity from 4G to 5G that, if affordable, could prepare a robust foundation for a digital economy.

The financial sector is not intermediating savings to the most productive uses, affecting capital accumulation as discussed in Chapter 3. As Pakistan’s finance sector falls short on diversification and depth, credit provision is low to begin with. However, in addition, rising government borrowing has crowded out credit to the private sector, so that private businesses receive just 40 percent of bank credit. The available credit to the private sector is heavily tilted toward large firms, with a mere 0.4 percent of bank borrowers accounting for 65 percent of all bank loans (SBP, 2015). SME loans comprise less than 10 percent of all loans in Pakistan compared with 15 to 20 percent in China, Bangladesh and India (Aslam and Sattar, 2017). Political connections bias credit allocation: a small number of influential firms receive a large share of the credit, despite higher default rates, causing annual losses estimated at 1.6 percent of GDP (Khwaja and Mian, 2005). Market failures also affect credit allocation. Reform efforts to address this, such as the Secured Transactions Act, aim at mitigating market imperfections related to risk and informational asymmetry for SMEs, have been slow in Pakistan.

Power supply and demand are poorly coordinated in Pakistan’s energy system, leading to shortages and surpluses that deprive firms of a key input to production and generate high fiscal costs. In the 1990s, Pakistan was one of the first countries in the region to introduce power sector reforms. This involved unbundling the integrated electricity utility, establishing an independent regulator and involving the private sector in generation. Despite these reforms, the lack of an arm’s length relationship between the government and public utilities has negatively impacted their transformation into commercially run and managed companies. Inflexible and long-term power purchase contracts in which most risks are passed on to the government-owned single buyer has reduced the incentives for generators to be efficient and responsive to changing demand conditions. As a result, while some distribution utilities have improved efficiency, others continue to suffer from high system losses and low collections. These utilities are unable to pay for power purchase costs and to make investments in the network, leading to surpluses and shortages, suboptimal allocation and distribution of natural gas, higher generation costs, and congestions in networks. Recent efforts, including the operationalization of the Central Power Purchasing Agency-Guarantee (CPPA-G) to develop a competitive electricity market and amendments to the sector law to liberalize the generation and retail markets, aim to enhance consumers’ and firms’ access to electricity, but are not yet completed.

Cities have not been able to play their role in supporting structural transformation because of ineffective governance and inefficient use of scarce resources. Government failures in Pakistan inhibit the role of cities to act as centers of growth for three main reasons. First, high and increasing institutional fragmentation with unclear accountability in governance structures reduces efficiency in the planning and delivery of city services. Municipal services are often provided by specialized entities with weak financial sustainability, which has an impact on fiscal sustainability and service delivery. Second, municipalities continue to remain financially weak, with high dependence on provincial transfers and grants. Urban property taxes, which are usually an important revenue source for cities, are collected by the provinces. Other revenue sources under municipal responsibility are not being fully utilized. There are also concerns regarding financial management practices and the efficiency of municipal finances. Third, weak planning practices and inappropriate/uncoordinated land management in the cities are leading to urban sprawl, the creation of slums, and inefficient spatial development. Major investments are generally undertaken through vertical programs, designed and implemented by higher levels of government without involving or consulting local stakeholders or accounting for their needs. This is leading to increasing costs of mobility and provision of municipal infrastructure and services, inefficient spatial development and a decaying environment, resulting in less livable cities.

Suboptimal corporate governance arrangements of SOEs limit the government’s ability to regulate SOEs, which can negatively affect private sector development. SOEs are a major instrument used to deliver publicly funded services. Pakistan’s federal government owns 197 SOEs, with a combined output of 10 percent of GDP and combined assets valued at 43.4 percent of GDP in FY16. The portfolio includes not only natural monopolies (for example, railways), but also industries that are typically the domain of the private sector. Legal ownership of the SOEs lies with the government of Pakistan, but in practice the line ministries exercise the ownership and oversight functions over the SOEs in their sectors. Line ministries exercise these functions by appointing their own officials to SOEs’ Boards of Directors, despite regulatory requirements that mandate the appointment of independent Board members. This arrangement gives rise to conflicts of interest between line ministries’ policy and regulatory functions, on the one hand, and their interests as de-facto owners of SOEs in their respective sectors on the other hand. This not only adversely affects SOEs’ operational performance, but it can also have negative externalities on the private sector, where preferential treatment of SOEs in areas such as credit provision can crowd out private sector opportunities.

Financial support to underperforming SOEs is a major driver of the fiscal deficit and a source of substantial fiscal risks. In FY16, subsidies, loans and grants to support federal SOEs accounted for 32.7 percent of the budget deficit and 1.5 percent of GDP. At the same time, public guarantees for SOEs pose significant fiscal risks, as they accumulate contingent liabilities for the federal government, reaching almost 3 percent of GDP in FY17. This is particularly problematic in the power sector, where shortcomings in the operations of DISCOs and the tariff-setting mechanism are direct and major causes of PKR 1 trillion of public debt. In addition, increasing reliance on fuel imports for power generation exposes Pakistan to significant fuel price and exchange rate volatility. On a net basis, fiscal support to SOEs significantly outweighs the profits that the public sector receives from them. For example, in FY15, the government’s receipts from SOE dividends covered only 28.6 percent of subsidies paid to them.

b. Absence of a coordinated policy response

A second constraint to structural transformation is the absence of effective government interventions to address market failures. Market failures often relate to the existence of positive externalities (such as in training or technology adoption) or coordination failures (such as in the formation of clusters). The experience of successful clusters in Pakistan suggests that even in a constrained overall business environment, policy support can make a difference in addressing market failures. Such a policy response may be necessary to improve coordination or internalize positive externalities. The successes of countries such as Japan, the Rep. of Korea and China show the role that governments can play in addressing market failures. The governments of these countries consistently promoted export growth and upgradation in selected sectors through various incentives, including easier access to credit, technology imports and foreign know-how. At the same time, they coordinated this support with other policies, such as the promotion of university and industry linkages in skills development and R&D (Chaudhry and Andaman, 2014).

Pakistan has not been able to support industrial clusters through the design of a coordinated policy response. Examples of the lack of a consistent strategy to support the shift to higher value-added products include the textile sector, where firms complain that they do not invest in machinery due to policy uncertainties in the sector (PIDE, 2018). There is also no policy initiative to identify new sectors in which there is potential for Pakistan to grow and move up the value chain. Early attempts to support industrial sectors included easier access to credit to large industrialists, import duty exemptions for certain industries, and preferential access to foreign exchange for exporters. But this support was not made conditional on performance, unlike other successful East Asian countries. Partly as a result, Pakistan’s industrial base is less competitive than those of other countries in the region. The Sialkot cluster is a well-known exception. Firms in the cluster argue that coordinated policy support contributed to their success, including the creation of a specialized industrial area in the 1960s that offered land to firms at 50 percent of the actual land value, and a scheme to promote non-traditional exports by offering duty rebates on inputs.

SEZs and industrial estates have failed to leverage agglomeration economies. SEZs and industrial parks can serve to coordinate government efforts by ring-fencing regulatory reforms and easing access to wellserviced industrial land. Both can enable agglomeration economies. However, Pakistan has not had positive experiences with industrial estates to date and this in turn makes firms wary of SEZs. Many industrial estates suffer from mismanagement and a lack of basic services and infrastructure. Unless firms are convinced that SEZs and industrial estates will become fully functional, their effectiveness as a tool for policy coordination will remain limited.

Missing skills and managerial capabilities constrain technology upgrading and innovation. The lack of basic firm capabilities such as skills and managerial capabilities deters technology adoption. In the textile sector, for example, firms highlight the poor quality and relevance of workforce skills as a constraint to productivity, product quality and upgrading (PIDE, 2018). Most firms in Pakistan are poorly managed by international standards (Lemos et al., 2016). The complementarity between basic firms’ capabilities and innovation is a key challenge for innovation in countries at Pakistan’s development stage (Cirera and Maloney, 2017). The underinvestment in market-relevant technical/vocational skills and in managerial skills are both a kind of market failure that requires a well-coordinated policy response.

Poorly functioning land markets constrain firms from locating efficiently. This in turn limits access and mobility, preventing agglomeration economies from materializing. Land and housing prices have risen considerably over the past two decades, making them unaffordable for low-income residents and smaller businesses. Real estate is also prone to speculative buying and holding, which reduces productive use of available land. Moreover, inefficient title registration is a significant factor impacting the housing market and the ability of firms to expand or relocate, as land cannot be used for collateral and land acquisition is cumbersome. Similarly, the mechanism for registration of property transactions is inefficient, often involving multiple agencies. For instance, more than 17 different agencies are involved in land titling and registration in Karachi.

c. Limited trade and regional integration

Pakistan has failed to reap the benefits of trade and regional integration. Pakistan’s trade-to-GDP ratio was close to that of its South Asian neighbors in the early 2000s, but then fell behind as Pakistan failed to fully leverage export trade as an engine of growth. From 2005 to 2017, India’s exports of goods and services increased by 216 percent, Bangladesh’s by 250 percent, and Vietnam’s by 519 percent. In comparison, Pakistan’s exports increased by only 50 percent, from US$19.1 billion to US$28.7 billion. In addition, access to international markets has helped firms in South Asia to grow and become more productive. There are many channels through which trade has promoted productivity growth: competition, knowledge spillovers, and access to better technology and quality inputs. Bangladesh’s garment industry and India’s auto industry are some of the well-known success stories. But Pakistani firms have not been able to fully leverage the potential of trade because of trade policy constraints, logistical issues and limited regional integration.

Pakistan has relatively high tariffs and has often used regulatory duties to curb imports. The trade policy liberalization of the 1990s has suffered a reversal, and Pakistan still has relatively high tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade. Today, Pakistan’s tariffs are three times higher than those in Southeast Asia More importantly, Pakistan also has one of the highest weighted average tariff rate differentials in the region, with an average tariff difference between consumer goods and raw materials of 10.39 percentage points in 2016, and between intermediate goods and raw materials of 2.21 percentage points. Tariff differentials generate an anti-export bias, as they provide strong incentives for Pakistani firms to sell domestically where they are sheltered from competition. Trade policy has also discouraged foreign firms from considering Pakistan as a destination for efficiency-seeking investments. As a result, Pakistan’s exports have remained stagnant, undiversified and unsophisticated.

Regulatory duties (RDs) and firm-specific exemptions have been used in Pakistan with the effect that competitive pressures are muted. The number of tariff lines affected by RDs increased from 0.4 percent in 2013 to 12.6 percent in 2017. Almost 75 percent of customs duty exemptions are claimed by the largest 100 firms (World Bank, 2016). Sector-specific policies also affect competitiveness; firms in the textile sector complain that a policy of not allowing imports of high-quality yarn has constrained quality improvement in clothing.

Pakistan’s inward-oriented trade policies have stalled Pakistan’s integration into regional and global value chains. Modern-day production networks rely on the components of final products being able to move quickly and cost efficiently among multiple countries. To facilitate integration into these networks, countries have made efforts to reduce trade costs, which Pakistan has not done. The increased use of adhoc tariff exemptions for imported intermediates has benefited mainly a few large firms, but put small and medium exporters, including highly innovative firms, at a disadvantage.

Customs clearance and transportation are the main logistical challenges to trade. In 2015, it took exporters 141 hours and importers 294 hours to clear customs at Karachi, compared with 20 hours and 13 hours, respectively, in the OECD (World Bank, 2016). Despite recent improvements in logistics performance, poor levels of trade facilitation continue to inhibit export competitiveness and trade growth. There is a critical need to improve customs and border management to lower logistical costs, particularly port operations and customs procedures.

South Asia is the least integrated region in the world, limiting the benefits from regional integration. This affects not only trade, but also investment, movement of people, connectivity and regional value chains. This lack of regional integration is even more apparent if the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) is compared with more functional regional blocks, such as APEC, ASEAN and NAFTA (Figure 28). Greater integration will require reciprocal liberalization by all countries and, for example, Pakistan faces higher protection from its neighbors India, China and Bangladesh than it does from the EU, UAE and the United States. Notwithstanding various bilateral trade agreements, Pakistan’s trade share with neighbors—with the exception of China—is negligible (Figure 29). Strained regional relations have constrained economic cooperation, preventing Pakistan from leveraging its geostrategic location to become a trade and transit hub, at the intersection of energy-rich Central Asia and the Middle East, and two of the world’s fastest growing economies, China and India.

Trade with the region could more than triple. Pakistan’s share of exports to India is less than 2 percent of its total exports, while India’s imports from Pakistan account for less than 0.5 percent of its total imports. Trade with India could increase 18-fold, with exports growing 45 times over their 2015 value and imports growing 15 times over the same period (as suggested by gravity-model analysis in Table 2). In addition, due to the proximity and size of the Indian economy, predicted exports to India are 3.5 times higher than those predicted for China. Overall, liberalization of trade in goods with the region could result in the economy growing by 30 percent by 2047. This does not take into account the potential for increased trade in services, investment or the formalization of informal trade. Transit trade for Afghanistan and Central Asia also holds great promise for Pakistan, particularly now with CPEC-related infrastructure and logistics improvements.

Table 2: Potential trade estimates

| Country | Current trade with Pakistan (2015) (US$) | Predicted trade with Pakistan (US$) |

|---|---|---|

| China | 12,953,931,121 | 18,870,219,582 |

| Afghanistan | 2,112,616,630 | 2,112,616,630* |

| India | 1,981,570,462 | 35,637,743,064 |

| Bangladesh | 760,816,411 | 760,816,411* |

| Sri Lanka | 332,270,224 | 332,270,224* |

| Iran | 293,187,399 | 293,187,399* |

| Turkmenistan | 22,878,000 | 22,878,000* |

| Kazakhstan | 16,561,000 | 24,441,417 |

| Tajikistan | 4,074,000 | 4,317,138 |

| Uzbekistan | 3,097,000 | 14,919,881 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 914,000 | 3,809,115 |

| Total regional trade | 18,481,916,247 | 58,077,218,861 |

* For these countries, current trade is already more than predicted trade, so current trade is reported instead of predicted trade.

Strained regional relations affect trade, opportunities for regional cooperation and countries’ domestic policies. Strained relations have affected trade and investment volumes, but also countries’ ability to use regional cooperation to address issues that would benefit from regional coordination, such as security and climate change. The benefits of greater regional integration are broader than the limited discussion on trade in this chapter (see Burki, 2007, for a more detailed estimate of the costs of the tensions with India for Pakistan). Strained relations also affect domestic policies. Pakistan has allocated a large amount of resources to developing and maintaining strong military capabilities. Pakistan’s spending on its military detracts from how much it can spend on other development priorities (Figure 30), with less resources available to meet its development needs than peer countries. The smaller size of its economy vis-à-vis India (and the growing gap) means that, although as a share of GDP military spending is significantly higher than India’s, in absolute terms it is vastly outspent by India (Figure 31).

Increased regional integration will support structural transformation and a stronger economy. In recent times, global security policy discourse has increasingly emphasized the need to also invest in economic and human development as a way of ensuring security. Today, as Pakistan embarks on its third consecutive term of democratic rule, the institutional imbalance between a powerful military and an underdeveloped political system continues to dominate policies, leading to traditional thinking about regional security. This traditional approach, however, is becoming increasingly unsustainable, as suggested in Figure 32. A strategy that makes full use of Pakistan’s geographical position, transforming the country into a trade and transit hub, will result in a stronger economy, able to invest adequately on its physical and human capital. This strategy could in the long term be significantly more successful in contributing to Pakistan’s security and territorial integrity. As Pakistan invests in regional connectivity, acts as a transit hub for the neighborhood and develops stronger regional relations, regional integration should increase its leverage to resolve disputes with its neighbors over time.

Governance: A Cross-cutting Issue

Weak governance is a cross-cutting constraint that affects Pakistan’s ability to transform its economy. Most constraints to economic activity reported by Pakistani firms can be traced back to issues related to governance (corruption, electricity, taxation). Good governance is a necessary foundation for consistent, well-designed and well-implemented policies (World Bank, 2017). Weak governance makes it easier for powerful groups with narrow interests, such as politically connected firms, to exert undue influence over policy. Policy capture can take a number of forms, including the design of market regulations to favor connected firms, the location of industrial zones to favor private interests, or the imposition of trade barriers to benefit lobby groups and labor unions.

Policy capture may be behind some of the constraints to structural transformation in Pakistan.

Pakistan is inherently susceptible to policy capture because of a historical concentration of economic power among large industrialists and landowners. In the 1960s, the chief economist of the planning commission, Mahbub ul Haq, claimed that 22 families controlled 66 percent of the industrial wealth and 87 percent of banking and insurance. More recent analysis suggests that elite capture continues to constrain economic policymaking (Husain, 1999; Ul Haque, 2017). Since the 1980s, the share of industrialists in the National Assembly and Parliament has doubled, blurring the barrier between politicians and businessmen. Policy uncertainty and a lack of trust in policy implementation affect firms’ reactions to reforms and may affect the effectiveness of otherwise well-designed and implemented policies.RECOMMENDATIONS

Structural transformation, by allocating capital and labor to more efficient sectors, firms and uses, is a key process through which productivity and hence incomes increase. In the same way that market and government failures affecting structural transformation are not confined to a single sector but widespread in the economy, the set of reforms to address these constraints also affects many sectors in the economy. This chapter discusses the general direction that reforms which are more narrowly linked to structural transformation could take to improve productivity and accelerate growth in Pakistan. Among the reforms discussed, two types should be prioritized. First, reforms that improve the regulatory business environment offer an accessible pathway to attracting investment in the near term but remain a continuous process that should be sustained through the medium term. Second, a more open trade and investment regime can improve firms’ incentives to innovate and enhance productivity by exposing them to competition and facilitating access to the latest technologies. Other important reforms include investment in managerial and basic labor skills, reforms to SOEs, particularly in the energy sector, and efforts to improve urban development. Government support for technology transfers and extension are likely a more effective policy in the medium term.

For a detailed discussion of suggested reforms please refer to the Pakistan@100 policy notes ‘Structural Transformation in Pakistan’ and ‘Building a Case for Regional Connectivity’. Reforms in the agriculture sector are discussed in the following chapter.

a. Reforms to address government failures that constrain structural transformation

Reforming business regulation. Cumbersome business regulations mean that firms spend valuable resources on navigating the regulatory environment without putting them to productive use, which reduces their productivity. Regulatory reform should level the playing field for all firms by reducing red tape, and the scope for excessive discretion and arbitrariness in enforcement. Pakistan has already embarked on these reforms as part of the ‘Doing Business Reform Sprint’, which is driven by a high-level committee established by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO). This reform initiative should be deepened and expanded to address the myriad layers of regulations at the federal, provincial and local levels, as well as sectorspecific regulations. Potential interventions should aim at reducing the procedures, costs and time associated with investing and doing business in Pakistan, aligning the national investment policy with sectoral policies, streamlining the FDI approval process, and consolidating the multitude of incentive schemes by establishing a one-window operation. The reform agenda could be driven by a ‘National Business Climate Reform Unit’ attached to the PMO, supported by complementary organizations at the provincial level. For instance, Punjab has a functioning Investment Climate Reforms Unit. The roles, responsibilities and powers of these units should be clarified and formalized through guidelines or new laws, as necessary.

Increasing transparency in the regulatory environment and facilitating compliance. Regulatory reform can be complemented by measures to improve transparency and ease of compliance for firms, starting with a comprehensive inventory of all the licenses and permits that apply to firms in each province or sector. This could be used to prepare and maintain updated, consolidated regulatory repositories that list all requirements and procedures, at both federal and provincial levels. Furthermore, regulatory compliance could be eased through single-window online portals for registration and other compliance activities.

Investing in digital infrastructure. Digital technology has been a key driver of productivity improvements in recent decades. Going forward, 5G mobile networks hold great promise as a facilitator for digital development in Pakistan. These networks rely on the national fiber optic network owned by the state operator, Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited (PTCL). The national fiber optic network is the main transmission network and links to the international terrestrial and submarine networks. Improvements in unrestricted access to PTCL’s network would benefit the private operators. Similarly, a further network expansion and quality improvements would improve mobile broadband access and could ensure access in under- and unserved areas. Digital development should further come with safeguards including national cyber security and personal data privacy. At the same time, providing an enabling environment for a competitive and open market for telecom and digital players, and digital skills for potential employees, is critical to ensuring the meaningful uptake of digital solutions.

Completing power sector reforms. To improve firms’ access to electricity to allow them to operate more productively, existing power sector reforms should be completed and complemented. CPPA-G is still in transition to becoming the market operator and much preparatory work is needed for the wholesale electricity market to be ready by 2020 as scheduled. Moreover, the current National Power Control Center needs to be strengthened to deliver the critical role of a modern system operator to plan reliable and leastcost dispatch to benefit the additional generation capacity, and to enable transparent and non-discriminatory third-party access to networks and wholesale competition. The transmission grid needs significant investments to provide the highway for energy generated to where the demand is. Finally, there is a need to improve the operational performance of public distribution utilities and put in place systems to control technical and commercial losses, so that these entities become credit-worthy to undertake the required investments.

Improve urban planning to benefit from agglomeration economies. The provincial governments need to ensure coordinated urban and regional planning is undertaken across entities, with a coordination mechanism for agencies that cover multiple jurisdictions. Regional planning should also include integrated transportation and land use planning, and promote the development of satellite cities and industrial clusters, enabling agglomeration benefits. Moreover, city strategic development plans need to be developed by municipalities of each city and town through an extensive consultative process with key stakeholders including citizens, private sector, civil society, land-owning agencies etc., as part of a “growth coalition” for the city.

Improving corporate governance and reducing distortions emanating from SOEs. To mitigate the risks emanating from SOEs, Pakistan requires a new SOE policy that defines the purpose of government ownership. The policy needs to set explicit objectives, such as the generation of non-tax revenues, or the provision of public goods and services in areas of market failure. Following this, the government must identify SOEs that should be privatized and ensure completion of the privatization process in a transparent manner. After deciding on the scope of the reformed SOE landscape, it will be crucial to develop a clear, coherent, and modern legal and regulatory framework for the state as the owner and shareholder of SOEs, separating the functions of the state as a regulator and owner of SOEs. This would entail an ownership policy that defines how the state governs its SOEs, thereby laying down clear criteria for subsidizing SOE activities and extending financial support to the SOEs. This also entails designating a central entity to manage the SOE portfolio, tasked with monitoring and reporting on the financial performance, fiscal risks, and regulatory compliance of individual SOEs and the SOE portfolio, as well as developing a performance framework for SOEs in collaboration with their respective line department. Finally, improving corporate governance entails appointing independent management boards for SOEs to separate the government’s role, as owner, from its role as policymaker, coordinator and regulator.

Mandate financial reporting and consolidate public support. To ensure transparency, it is key to mandate SOEs to use International Financial Reporting Standards and publicly disclose annual financial statements and external audit reports. Similarly, it is key to make further financial support to SOEs conditional upon improved financial performance based on specific targets that are set in performance agreements. Instead of covering the operational losses of SOEs, government subsidies need to be limited to SOEs that provide public services and be calculated based on outputs (e.g., additional MW of power generated) and unit costs. To implement these changes effectively, the government will need to strengthen the mandate of the Ministry of Finance to hold SOEs accountable for their financial performance. The Ministry of Finance will also need to account for contingent liabilities arising from government loans and guarantees for SOE borrowing, which has grown in recent years and poses significant fiscal risks.

b. Reforms to address market failures that constrain structural transformation

Modernize land management to encourage efficient use of land resources. These efforts should include development of a comprehensive framework for land records in urban areas through an automated and streamlined urban land records management system, including one-window facilities for urban land transactions in major cities. To reduce inefficiencies in land use, a unified land-titling system should be introduced. Moreover, land use conversion processes should be streamlined to encourage commercial real estate development. Reforms should be undertaken for more productive use of state land through the release of vacant state-owned land for productive and economic uses in city centers to better exploit the economic and social potential of this scarce asset. Lastly, medium and high-rise multiple ownership housing facilities should be developed to densify urban development, reduce sprawl, promote compact cities and increase the supply of housing, especially rental housing

To support innovation, Pakistan should adopt a phased approach, starting with investments in basic skills and managerial capabilities. Market failures affect the resources that firms are willing to invest in skills (basic skills, managerial capabilities) and acquiring new technologies, thus constraining human capital accumulation, as well as productivity improvements. Most firms in Pakistan are at a stage where the adoption of basic managerial practices, machinery upgrading and basic process improvement are more relevant than R&D. Public support should therefore focus on management extension programs to ensure that technology is accessible, and on strengthening the “absorptive capacity” of firms to facilitate technology transfer (e.g., through the Small and Medium Enterprise Development Agency, or SMEDA). During the first phase, support should also be provided to investments in education and R&D to create a pool of entrepreneurs and high-skilled workers. Support in achieving quality standards and quality certification will help firms seeking to break into new export markets, particularly for smaller firms. Strengthening the infrastructure for testing and certification will help them avoid the more expensive option of having to seek certification in a third country.

In a second phase, support could be provided for technology extension. Firms’ investments in newer technologies, and their capacity to generate and absorb new technologies—a key driver of productivity increases—is also affected by market failures, lowering their capacity to innovate. As firm and institutional capabilities grow, the mix of innovation polices should also evolve. As more firms and clusters develop the capacity to undertake more advanced innovation, the demand for sophisticated forms of support will increase. Programs could include technology extension support to more advanced clusters, or the settingup of “technology centers” to provide a combination of business, managerial and technical advice to SMEs. Knowledge management and transfer initiatives, especially with regards to modern technologies, offer a complementary pathway to facilitating technology adoption. Other forms of support could include grants for industry-research collaboration, and grants for innovative projects to finance prototyping, testing and commercialization activities and technical assistance.

A second phase would also see support for export clusters. Increasing exports through dedicated clusters does not only contribute to growth directly, but can also attract FDI and trigger technology transfer and productivity improvements. Supporting export clusters could follow lessons from the experience of East Asian countries. Sectoral development strategies took the form of coordinated support along multiple dimensions: at times providing financial support combined with incentives for technology upgrading through imported capital or collaboration with foreign investors or multinational enterprises. The strategies also coordinated sector-specific incentives for export promotion and upgradation with more general investment in skills development and industry-research collaboration. A cautious approach will be necessary, with emphasis on institutional capacity building, piloting, monitoring and evaluation, and a readiness to close programs if they are not working.

c. Reforms to improve trade policy and enhance regional integration

Trade liberalization. Establish a simple, transparent tariff structure with reduced tariffs, and with clear and transparent rules governing the use of discretionary provisions, including a uniform, less discretionary duty exemption scheme for exporters. Identifying and implementing key regulatory reforms in the services sector could improve Pakistan’s international competitiveness in the tradeable services and manufacturing sectors that are increasingly reliant on professional services inputs, such as logistical and financial services.

Trade logistics. Improving trade logistics through procedural facilitation and infrastructural improvement will also be critical. An automated internet-based processing system for border management has already been rolled out. This roll-out should be completed and extended to all relevant regulatory agencies. Assessing and subsequently upgrading the biggest infrastructural bottlenecks at borders, such as inadequate weighbridges and scanners, sheds and warehouses, customs facilitation centers, and quarantine and phytosanitary facilities, should be undertaken. Adopting a more modern risk-based compliance management strategy for border controls will help focus attention on the most high-risk consignments, while expediting those that do not pose serious issues.

Enhance regional integration:the first phase. The process of unlocking Pakistan’s regional promise must start with a consensus across Pakistan’s leadership, and between civilian and military leaders, to use constructive regional relations to support economic competitiveness and growth. The current strategy, focusing primarily on a strong and capable military does not seem sustainable. A number of steps can be taken toward greater integration with the region, in addition to the steps described above to liberalize trade and improve logistics. These include using CPEC to improve relations with other countries that could benefit from it, including Iran, Afghanistan and those in Central Asia. To improve relations with India, the two countries could revitalize the Pakistan-India Joint Chamber of Commerce, normalize visa processing, including for business people, and enter into a dialogue on trade liberalization measures.

Enhance regional integration: the second phase. In the medium term, Pakistan could deepen some of the reforms undertaken in the short term, including opening up other border points with India, such as Khokhrapar-Munabao in Sindh and Sialkot in Punjab. Border infrastructure such as warehouses and improved cold-storage facilities would be necessary to facilitate increased trade between the two countries. Railway links to carry both passengers and freight from borders and ports to Pakistan’s major cities are needed to reduce transportation costs. On the western border with Afghanistan, similar investments in improved border infrastructure, customs procedures, and road and rail connectivity would expand trade capacity and foster domestic manufacturing growth in Pakistan. Other efforts to increase regional integration as relations with neighbors strengthen might include: inviting multi-country involvement in CPEC (including India); offering India an overland route to Afghanistan in return for gaining access to Central Asia for itself; offer both Karachi and Gwadar ports for use to all neighbors; and work with Iran to develop synergies and complementarities between the Gwadar and Chabahar ports. Pakistan should push for the timely completion of connectivity projects already committed to by all countries in the region.