Accumulation

Accumulation of human and physical capital is necessary for accelerating and sustaining high growth. Countries that sustained high economic growth for extended periods put substantial efforts into raising public and private investment rates by increasing domestic savings, creating an enabling environment for foreign direct investment (FDI) and deepening their human capital to improve health and education outcomes for their populations (Growth Commission Report, 2008). For Pakistan to sustainably accelerate growth, it must do the same and sustainably increase investment levels.

This chapter discusses factors that have constrained the accumulation of human and physical capital in Pakistan and recommends policies that would help Pakistan to overcome these constraints. Pakistan has historically had low levels of investment in human and physical capital. This chapter is divided into two parts. The first part discusses human capital investment and the second focuses on physical capital investment in Pakistan. The chapter concludes with recommendations for addressing the challenges identified.

PART 1: HUMAN CAPITAL

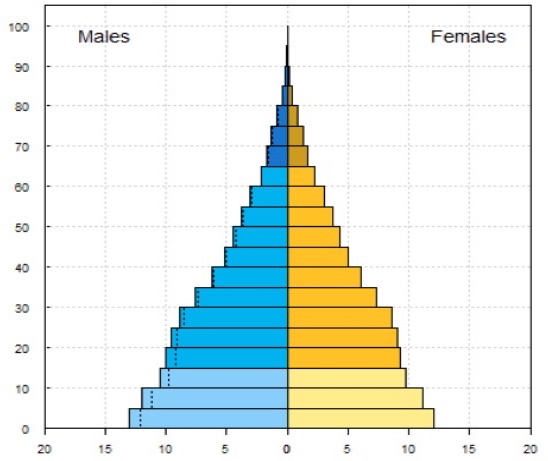

Pakistan’s large and growing population of almost 208 million is its main asset. Pakistan is experiencing a youth bulge with the number of individuals entering the labor market over the upcoming years expanding at a faster rate than the total population (Figure 6). Given this abundant labor supply, investment in human capital and its utilization is critical to stimulating growth. Pakistan’s youth bulge can be turned into a demographic dividend if the economy is able to absorb the substantial number of young workers entering the labor force by creating sufficient quality jobs, and ensuring that individuals of working age—both men and women—participate in the labor force and are equipped with the right skills. Increasing female labor force participation could give growth a significant boost, which will require significant investment in human capital, with particular attention to closing existing gender gaps.

Human capital enhancement requires investment in each stage of the life cycle. Human capital accumulation is a dynamic process that begins before birth through investments in maternal health and nutrition, continuing through early childhood development, and further through schooling and labor market experiences. The well-known expression “skills beget skills” captures the continuum of human capital investment. Investing in skills and labor—the most important assets of the poor—to enable the accumulation of more skills, whether through improved nutrition, stimulation at home, formal education or labor market experiences, and utilizing human capital in an efficient way is the most sustainable way to help individuals benefit from and contribute to the economy’s growth.

Pakistan is currently experiencing a growing working-age population and a declining dependency ratio—demographic changes that tend to be favorable for growth. Between 2004 and 2015, the country’s working-age population grew by 2.4 percent per year, whereas the total population growth rate over the same period was about 2.1 percent per year, with a declining dependency ratio. Moreover, the labor force grew more rapidly (by an average of 2.9 percent per year) than working-age population growth, indicating a favorable condition in the labor market.

Despite these favorable transitions, Pakistan is not fully benefiting from them due to underutilization of human capital. The growth rates of non-agricultural employment and paid employment are only 1 and 4 percentage points greater than that of employment growth. This suggests slow job creation in the nonagricultural sector and in paid employment, which typically are job-creating sectors in dynamic economies. For instance, in Bangladesh, where the ratio between the working and non-working age population is also growing, the labor market shows far more rapid growth in non-agricultural, wage employment than in total employment. In addition, real wage growth among paid employees in Pakistan grew only by 1.5 percent per year, which suggests only modest improvement in the quality of jobs or labor productivity.

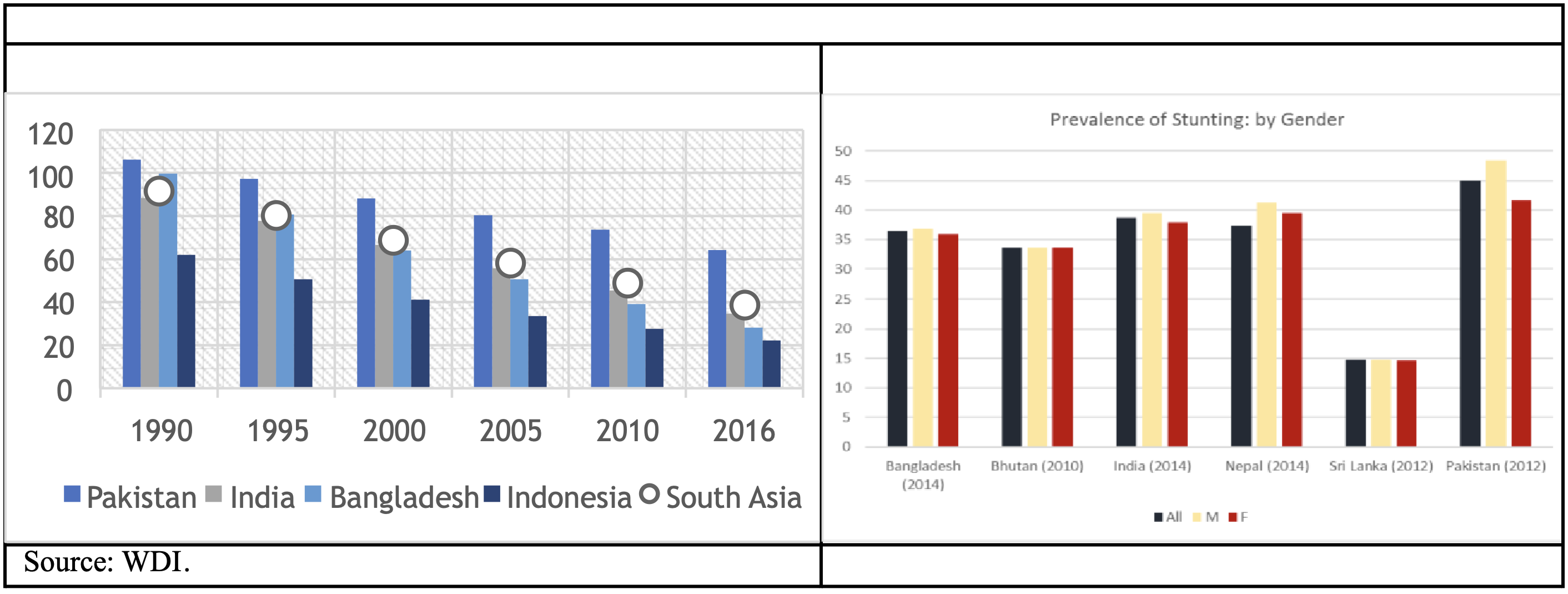

Pakistan’s labor productivity needs faster growth to improve the country’s competitiveness. Labor productivity measured as GDP per person employed implies that Pakistan’s labor productivity is stagnant, with its growth rate being the lowest in the region and far below the average of lower middle-income countries (Figure 7), affecting competitiveness. This contrasts with comparator economies such as India and China where average labor productivity growth rates over 2003-14 were 6.3 and 9.2 percent, respectively.

Human Capital Diagnostic for Pakistan

Improving human capital accumulation requires a life-cycle approach. The discussion below focuses on four critical pillars of human capital accumulation. Focus on these pillars can help policymakers design and implement key policy measures to boost the country’s human capital and labor productivity. The lifecycle approach highlights the importance of early intervention, where the returns to investment are larger at earlier stages of the life cycle. While the pillars are presented separately, it is worth noting that these policy areas are inter-connected given the continuous nature of human capital accumulation.

a. Pillar 1 - Informed Decisions on Parenthood

Lower fertility and better reproductive health are associated with improved maternal and child health, and also greater female labor force participation. Evidence reveals that women who delay, space, or limit childbirth have more opportunities to allocate their time and resources toward investing in each child’s health and education, leading to a reduced fertility rate, higher birth weights, lower levels of child mortality, better child nutrition, and improved cognitive development (Barham, 2009; Nishta, 2005). Access to reproductive health services and family planning helps women better control the timing and number of births, which in turn enables women to redirect resources toward schooling, job training, and working outside the home. Moreover, children who have benefited from their mother’s quantity-quality trade-offs may also be presented with greater opportunities in the future (Joshi, 2012).

Lowering fertility is a precondition for Pakistan to realize its demographic dividend. A demographic dividend occurs when dependency rates decline and this boosts growth, partly through increased savings and investment, and increased female labor participation. As countries develop, they tend to move through the various phases of the demographic transition process. In the first phase, the increase in the number of children is proportionally larger than the increase in the working age population, leading to a decrease of working age population share. As income and education improves, fertility and mortality rates decline, and there is an increase in the share of working age population. This is the stage of the demographic transition that provides the initial condition for the demographic dividend. Further declines in fertility rates will be necessary, together with simultaneous improvements in educational attainment and labor productivity for Pakistan to benefit from a demographic dividend. (For more details, refer to the Pakistan@100 policy note ‘Human Capital’.)

Pakistan continues to have substantially higher fertility rates than its peers, with little progress in reducing them over the past 25 years. While rapid fertility declines were observed in the 1990s, fertility rates have leveled off since the early 2000s. In 2015, women in Pakistan had an average of 3.7 children, higher than many regional counterparts (Figure 8). Considerable disparity in fertility rates persists across regions—women in urban areas have 3.2 children on average, compared with 4.2 children per woman in rural areas. In the context of Pakistan, where out-of-wedlock childbearing is limited, the fertility rate is determined by a host of factors, including age at first marriage, marriage rate, and total number of children. Women who marry at a young age have a higher number of childbearing years, and hence higher total fertility than women who marry older. A host of other factors also come into play, including lower educational levels and limited understanding of family planning methods, which contribute to higher fertility.

The average age at first marriage and the marriage rate have not changed much for women in Pakistan in recent years. The median age at first marriage rose from 19.1 years in FY07 to 19.6 years in FY13 (DHS, FY13). Although urban women tend to marry slightly later than rural women, about 90 percent of women are married by age 30 in urban and by age 28 in rural areas. Moreover, early marriage is persistent in rural areas, with roughly 46 percent of women being married by age 20, and one-quarter by age 18.

Pakistan’s contraceptive prevalence (share of married women using modern contraceptive methods) rose from 16 percent in 1990 to 38 percent in 2006, but declined to 26 percent in 2012 (DHS, FY13).

The low rate of contraceptive use is striking, as knowledge of contraception is almost universal in Pakistan (almost 99 percent of women reported being aware of modern contraceptive methods). There are considerable disparities in contraceptive prevalence rates across provinces, indicative of varying sociocultural constraints, with the rate highest in Punjab (29 percent) and lowest in Balochistan (16 percent).

There is a notable difference between desired and actual fertility rates, which may indicate limited gender empowerment. On average, actual fertility rates tend to be greater than those desired, suggesting a failure of birth control. The gap between the two tends to be larger for less educated women living in poorer, rural households. Around 37 percent of episodes of contraceptive use were discontinued within a year of initiation, with 10 percent of women citing side-effects and health concerns as the basis for discontinuation. One-fifth of currently married women reported an “unmet need” for family planning services, indicating their lack of satisfaction in family planning. The incidence of unmet need for family planning is highest in the lowest wealth quintile (25 percent) and in Balochistan (31 percent).

b. Pillar 2 - Strong Start through Early Childhood Development

The skills developed in early childhood, from birth to primary school entry, form the basis of future learning and labor market success. The process of skill formation is dynamic and builds on itself. Fostering early-life skills facilitates the accumulation of skills over the life cycle, where future skills have intergenerational impacts. These dynamic relationships make early life an important period because it lays the foundation for building skills later in life (Garcia et al., 2017). Early childhood development enhances a child’s ability to learn, to work with others, to be tolerant and persistent, and to develop a wide range of other foundational skills for formal learning and interactions in the school years and beyond. Conversely, research demonstrates that the effects of adverse early childhood environments persist over a lifetime.

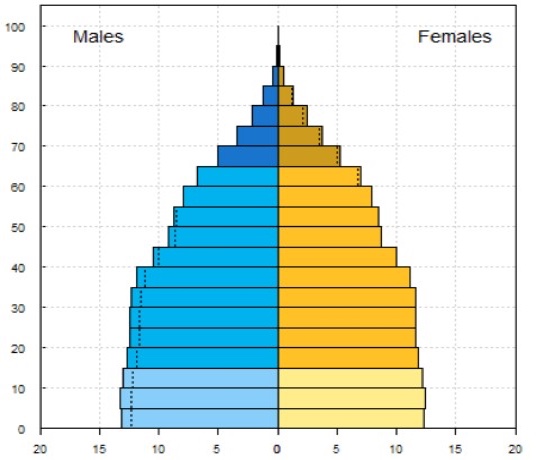

Pakistan lags peer countries in indicators related to early childhood nutrition and health. There has been a significant reduction in infant mortality rates over time, but compared with other countries the pace is slow and the level remains significantly higher (Figure 10). Pakistan has the highest rate of child stunting (height for age) in the region. With respect to being underweight (weight for age), Pakistan still shows worse outcomes than many other countries in the region, although the gap has been diminishing over time.

Nutrition outcomes are significantly different across wealth quintiles. This suggests that poor nutrition is most likely correlated with poverty, reflecting the inability of poor households to access basic health and nutrition services. However, at the same time, it is striking that almost 15 and 20 percent of children are stunted in Punjab and Sindh, respectively, even when mothers have more than secondary education, or the children belong to the highest wealth quintile households. This could reflect a general lack of awareness of diet and nutrition, as well as preferred feeding practices for the first 1,000 days of life.

The lagging outcomes of poorer households can reflect overall environmental factors that impact children’s health. For instance, the Water Supply and Sanitation (WASH) data show that there is a huge gap between urban and rural areas with respect to access to basic sanitation services. Despite significant improvement over the past decade from a very low base of 25 percent in 2005, only three-quarters of urban households and less than half of rural households had access in 2015. Similarly, the sewer connection situation also presents a dismal sanitation condition, which can lead to the transmission of diseases caused by inadequate sanitary services, including frequent bouts of diarrhea. While there has been overall progress over time, less than one-quarter of households had septic tanks and sewer connections in 2015. The share of households with latrines and other modern sanitation environment was also less than 10 percent.

c. Pillar 3 - Education and Learning for All

Education levels have been improving over time, but the pace is very slow. The gender and regional gaps in enrolment rates remain significant (Figure 11). In 2010, Article 25A of the Constitution declared education a fundamental right, following which laws were passed in each province that entitle all children aged 5 to 16 to free and compulsory quality education (ASER, 2017). Despite this, progress has remained slow, with the net primary enrolment rate increasing by only 2.4 percentage points from 64.6 to 67.0 percent between 2006 and 2015, whereas the gross primary enrolment rate has stagnated at around 90 percent since 2006.

Household incomes have a strong association with children’s school enrolment rates, suggesting that demand-side access is a significant determinant of education (Figure 12). The net enrolment rates range between 39 and 46 percent in the lowest quintile, and between 75 and 85 percent in highest quintile, across the four provinces. While the outcomes of the top three quintiles (Q3-Q5) show little variations, the outcomes of the bottom two quintiles lag behind, with the severity of the poor and non-poor gap varying by province. With respect to drop-out rates before the completion of primary schooling, the differences across income groups are much more pronounced in Punjab—38 percent of children aged between 10 and 18 drop out in the lowest income quintile, compared with 13 percent in the highest income quintile.

Not only the quantity but also the quality of education is concerning in Pakistan. In rural areas 48 percent of class 5 students and 83 percent of class 3 students could not read a class 2 story in Urdu/Sindhi/Pashto; 54 percent of class 5 students and 85 percent of class 3 students could not read class 2 sentences in English; and 52 percent of class 5 children could not do two-digit division (ASER, 2016). Learning outcomes may also be influenced by whether a child attends public or private school, as test scores are significantly higher in private schools (Andrabi et al., 2008).

Lack of progress in these outcomes could also be because of limited supply of schools and teachers compared with the increase in the number of students. The student-to-teacher ratio has been consistently increasing, with a sharp hike between 2013 and 2014 when it rose from 42.5 to 46.5. The share of trained teachers in primary schools also suggests that Pakistan is lagging behind other countries such as Malaysia and Vietnam. Moreover, teacher absenteeism and the quality of pedagogy are of serious concern, as almost 22 percent of public schoolteachers are absent at any one time and, even when present, they use ineffective teaching methods (Brown, 2017).

Pakistan is also faced with a serious challenge of out-of-school children, with an estimated 22.6 million children not attending school, 18 million of whom are between 10 and 16 years old (NEMIS, 2017). Baluchistan is home to the highest proportion of out-of-school children followed by the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). An estimated 30 percent of youth are also not in employment, education or training, including a staggering 54 percent of women (World Bank, 2018e). Demand-side socio-cultural barriers and bottlenecks influencing exclusion from school are related to society's attitude to gender roles, with girls facing restrictions on their mobility, and boys experiencing pressure to start contributing to household incomes. Girls are vulnerable to early marriage, causing them to drop out of school. Demand-side economic barriers include the costs of schooling. These include not only direct costs, such as expenditure on school materials, examination fees and transportation, but also the opportunity cost of a child's time (UNICEF, 2013).

d. Pillar 4 - Labor Productivity

To absorb the rapidly expanding labor force, the economy will have to create 2.1 million jobs annually. Given the large youth share in Pakistan’s demographic structure and expectations of increased female labor force participation, the economy will have to generate about 2.1 million jobs per year to accommodate the new entrants to the labor force. The quality of the jobs created also matters. The informal sector accounts for 72.6 percent of the employed population and the agriculture sector continues to employ more than 40 percent of the labor force. Reliance on agriculture for employment is more prominent among women, as over 70 percent of female workers are engaged in the sector, with most of them working as unpaid family workers. To achieve faster growth rates, the economy will have to create more and better paying skilled jobs.

Key characteristics of Pakistan’s labor market include the limited changes over the past few decades. Major labor market outcomes, including overall employment ratio, sector and status of employment, and formality rates, have not changed over the past decade (Figure 13). Female labor force participation (LFP) has modestly improved, largely due to an increase in rural women’s labor market activities, but nonetheless remains extremely low. Female LFP rate in urban areas has stagnated at around 10 percent over the past decade. The share of wage employment increased slightly, although the share of wage employment in 2014 for women is lower than that of 2005.

In a dynamic economy, as young people obtain better education than their older counterparts, they typically earn an increasing share of wage, non-agricultural employment. However, Pakistan’s youth do not appear to experience positive labor market transitions over time. Between 2005 and 2014, both youth and adults experienced less than a 2-percentage-point increase in the share of wage employment (from 40.3 to 42.1 percent for youth; from 38.8 to 40.7 percent for adults). With respect to non-agriculture employment, little progress (or even a regress) is observed, as the non-agriculture employment share decreased from 59.0 to 58.0 percent for youth, and slightly increased from 59.0 to 60.2 percent for adults.

Technical and vocational training can support the skilling of the existing labor force. The education system has not developed the skills needed in the labor market for a large proportion of the population. Pakistan needs to invest also in improving labor productivity of the existing labor force, not only children. Technical and vocational training covers only a small proportion of the labor force. There are 3,581 public and private vocational and technical public and private institutes, with a larger share of private vocational institutes than technical ones (NAVTTC, 2017). Only 6 percent of young people have acquired technical skill through the technical and vocational education and training (TVET) system, and only 2.5 percent of youth have received on-the-job training. Being in a TVET institution requires at least a secondary or higher secondary completion certificate, which is still limited to a small segment of the population. Some limited options exist for those unable to go through the education system, such as the Skills Development Council (SDC), a tripartite body with membership of employers, employees and the government. The SDC is reported to have a higher employment placement rate for trainees than for any other training institute, although its role after devolution in the complicated landscape of the TVET system is unclear.

The tertiary education landscape is rapidly expanding in Pakistan. Enrolments in tertiary education increased during the past decades from less than 2.7 percent of the college-age population in 2002 to 10.4 percent in 2015. Overall gender parity in higher education has almost been achieved (53 percent male and 47 percent female). However, large income and regional disparities still exist in access to tertiary education. According to PSLM data, only 0.4 percent of the poorest quintile participate in tertiary education compared with 17.3 percent in the highest income group.

Weak Policy Implementation: A Cross-Cutting Issue

Weak policy implementation has led to limited improvements in human capital. Over time, different governments have highlighted the importance of having quality education and health institutions, and introduced reforms to improve Pakistan’s performance in social indicators. However, as discussed above, Pakistan is still lagging in these critical sectors. Chapter 2 presents the elements of a working political system. In the social sectors, reforms are failing at the link connecting public officials to citizens (Figure 5, Chapter 2). Limited capacity, poor management and a lack of accountability at the local level have instilled widespread inertia in the service delivery system, and led to weak policy implementation and consequently few improvements in health, nutrition and education outcomes across Pakistan. With the devolution of service delivery to the provinces, the landscape has changed even more, and there is a need to improve coordination mechanisms and institutional frameworks for better results (see Chapter 5 on ‘Governance and Institutions’ for a more detailed discussion).

PART 2: PHYSICAL CAPITAL

Increasing investment from 15 to 25 percent of GDP is critical to unlocking Pakistan’s growth potential. Physical investment affects output and employment by feeding into an economy’s productive capacity, boosting both potential output and employment. It facilitates private sector development and contributes to productivity growth, often through critical investments in infrastructure. Low investment at around 15 percent of GDP poses key constraints for Pakistan’s long-term growth prospects, affecting both potential and actual growth. Pakistan’s investment-to-GDP ratio is low and has been continuously declining, particularly compared with trends in peer countries (Figure 14). A binding constraint to increasing investment levels is low domestic savings, and so attempts to increase investment will need to look at increasing domestic savings rates.

Understanding the Constraints to Investment in Pakistan

The following section discusses factors that have contributed to low investment levels in Pakistan. Factors that have historically constrained investment in Pakistan can be broadly grouped into two main categories, namely financing and low returns to investment. Low domestic savings and shallow financial markets restrict the supply of financing for investment. Low tax revenues and high current expenditures limit fiscal space for public investment. External financing in the form of FDI and domestic investment are constrained by a poor investment climate and a volatile macroeconomic environment.

Financing Constraints

Investment is constrained by limited supply of financing. This section discusses: (i) low domestic savings in Pakistan due to a high dependency ratio, limited financial inclusion and macroeconomic instability; (ii) poorly functioning financial markets due to lack of financial deepening and asymmetry of information; (iii) limited fiscal space due to low revenue mobilization and increasing expenditures; and (iv) low FDI.

a. Low Domestic Savings

Domestic savings in Pakistan at 13.8 percent of GDP (FY11-15) are very low. This situation compares unfavorably with those of neighboring countries. Savings as a share of GDP in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka were 29.7 percent and 24.5 percent, respectively, during the same period. Real savings rates during the past decade in these economies, proxied by real deposit rates (Figure 15), suggest that Pakistan’s savings rate was not only low but also volatile, which can adversely impact the ability of banks to lend the long-term credit needed for financing investments (Choudhary and Limodio, 2018). It is not surprising, therefore, that nearly all of Pakistan’s high-growth periods have coincided with abundant inflows of foreign savings (in the form of external loans, grants and remittances). Accordingly, whenever such inflows dried up, economic growth slid back, as domestic savings and investment were never sufficient to sustain the growth momentum.

High fertility rates have led to a high dependency ratio in Pakistan, which in turn has resulted in lower savings. Persistently high fertility rates in Pakistan have led to a dependency ratio above those of its peers (Figure 16), indicating the higher economic burden borne by the working-age population of Pakistan. Although this ratio has declined over time, Pakistan still has a higher proportion of dependent population than many of its peers. A high dependency ratio has various implications for the economy but has specifically been linked to low savings rates (IMF, 2005; Thornton, 2001).

Limited financial inclusion also adversely affects domestic savings and investments. According to FinDex 2017, only 21 percent of Pakistan’s adults have bank accounts, albeit up from just 13 percent in 2014, which puts Pakistan behind most of its peers. The increase in account ownership has not benefited all groups equally. In Pakistan, the gender gap between account ownership is almost 30 percentage points. However, this does not mean that adults in Pakistan do not save at all. As the FinDex report notes, Pakistan is among the few developing economies where 20 percent of adults cited savings as their main source of funds, but only 10 percent reported having saved in a financial institution, with the remainder saving in non-formal ways. This prevents a more effective financial intermediation of savings into investments.

Frequent cycles of macroeconomic instability have discouraged people from saving. Pakistan has a long history of macroeconomic instability, which has resulted in the country availing 21 programs from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) between 1958 and 2013. The negative impact of macroeconomic volatility on savings (through higher inflation) and investment has been well documented (Loayza et al., 2007; Aizenman and Marion, 1999).

b. Poorly Functioning Financial Markets

A relatively shallow financial market has been unable to fulfill the long-term investment needs of the private sector. The volatility in Pakistan’s macroeconomic environment has impeded the development of a well-functioning financial market. The banking sector’s deposit-to-GDP ratio was 37.6 percent at the end of June 2017. Most of these deposits are of shorter maturity, limiting the banks’ ability to provide longerterm financing. Meanwhile, private corporate debt markets have not developed, as very few companies have been able to issue long-term debt certificates to finance new investments or expansions. Between January 2014 and May 2018 only 11 term finance certificates (amounting to PKR 67.5 billion) were listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX), with mixed success, limiting long-term financing options. Asymmetry of information and limited financial literacy inhibit firms’ ability to overcome credit constraints. Survey evidence suggests that despite demand for capital, the inability of firms to provide reliable information makes banks reluctant to lend or only at very high rates. Financial literacy among small firms is limited. Many transactions in the SME sector involve informal and expensive trade credit (where the goods were bought and paid for at a later stage), which substitutes the need for formal credit.

c. Limited Fiscal Space

Limited fiscal space, the result of rigid current expenditures and low revenue mobilization, has given rise to low public investment levels. Figure 17 shows that public investment as a share of GDP is relatively low and on a general declining trend in Pakistan. Public investment in key infrastructure is considered important as a policy instrument, as it can crowd in private investment. However, low tax revenues and high current expenditures leave limited space for public investments. Current expenditures exhibit structural rigidities due to high debt-servicing costs, high defense expenditures, and significant subsidies, salaries and wages. Large fiscal deficits (which have been the norm) have been financed through commercial borrowing, which in turn has crowded out the private sector from the credit market during the past decade, and therefore limited private investment (Figure 18).

Source: World Development Indicators and World Bank staff calcultions

Source: State Bank of Pakistan (SBP)

As a result, public investment has been unable to remove infrastructure bottlenecks. Low public investment in important sectors, such as infrastructure, energy, human capital and transport has affected the country’s growth prospects. According to the Investment Climate Analysis prepared by the World Bank in 2009, the quality and availability of infrastructure, particularly energy, are important constraints to growth. Energy shortages have crippled industry over the past decade, while the underlying state of logistics in Pakistan lags that of most peer countries. Efforts to increase investment by relying on external financing need to be managed carefully to ensure debt sustainability and that investments generate the necessary returns. Current efforts to attract large investments into transport and energy generation through the ChinaPakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) hold significant potential, e.g. by adding significant electricity capacity, but also carry risks that need to be managed carefully.

Repeated efforts to increase tax revenues have been largely unsuccessful. While Pakistan’s economy grew in recent years, tax performance stagnated or increased at a slower pace and, in 2017, the tax-to-GDP ratio was 13.0 percent, against an average of about 20 percent for emerging economies but comparable with the performance of other countries in the region (in 2016 the tax-to-GDP ratio in Bangladesh was 8.8 percent, and 12.3 percent in Sri Lanka). Pakistan can improve its tax revenue performance to 15 percent of GDP in the medium term and 22.3 percent in long term (IMF, 2016). However, the narrow tax base, weak policy design, and ad-hoc policy changes have stalled revenue mobilization efforts. Preferential treatment toward certain sectors and tax exemptions have created further inefficiencies in the system. This has occurred despite the creation of numerous commissions, committees, task forces and other bodies to institute tax reforms.

Elite capture and corruption have added to the failure of tax reforms. As discussed in Chapter 2, critical reforms in several sectors including taxation have stalled due to opposition by privileged lobbies and interest groups, as evidenced in the incomplete implementation of GST reform, tax exemptions for the agriculture sector and an abundance of ad-hoc Statutory Regulatory Orders. Consequently, the government has been unable to broaden the tax net, particularly by reaching higher-income groups, increasing instead its reliance on indirect and withholding taxes. Furthermore, exemptions on agricultural incomes have resulted in tax evasion, as incomes from other sectors are falsely reported as agricultural income to receive exemptions (Khan, 2017).

d. Low Foreign Direct Investment

Pakistan’s share in overall global investment flows is low and falling. FDI has been declining (Figure 19) and is low compared with other countries. FDI is also highly concentrated in a small number of sectors and countries of origin. In the past 15 years, almost 60 percent of FDI has gone to three sectors: oil and gas exploration, communications, and the financial sector. Such high concentration means that negative developments in these sectors can have a disproportionate impact on overall FDI. In terms of FDI sources, the US, UK and UAE jointly contribute 60 percent of FDI, making Pakistan vulnerable to economic conditions or changing perceptions in these countries. More recently, much FDI has been coming from China under the CPEC initiative and has thus far been concentrated in energy and infrastructure.

To stimulate productivity growth, Pakistan needs to attract more FDI. FDI can be an important driver for supporting growth of exporting industries, but Pakistan’s ability to attract FDI into its export sectors has been inadequate and mostly limited to low-technology sectors. The share of services FDI going to low value-added services increased from 10.7 percent in 2005 to 62.6 in 2015, due to a decline in FDI in knowledge-intensive segments. Similarly, the share of manufacturing FDI going to low value-added manufacturing segments increased from 60.5 percent in 2005 to 93.9 percent in 2015. Pakistan needs to attract FDI in knowledge-intensive activities that can in turn have positive spillovers for the domestic economy. Greater integration in global value chains as a result of CPEC and related investments could also contribute to increased investment in higher value-added activities (World Bank, 2018f).

Profitability Constraints

Low returns on investments discourage private investment in Pakistan. Estimates suggest that returns to investments are comparatively low in Pakistan (see the Pakistan@100 policy note ‘Investment and Growth’ for details). This section focuses on factors that have led to limited profitability of investments in Pakistan, mainly (i) limited competitiveness, (ii) complex tax administration, and (iii) weak entrepreneurship. Underlying most of these issues is a generally weak investment climate, which is discussed in more detail in the next chapter on the allocation of resources.

a. Limited Competitiveness

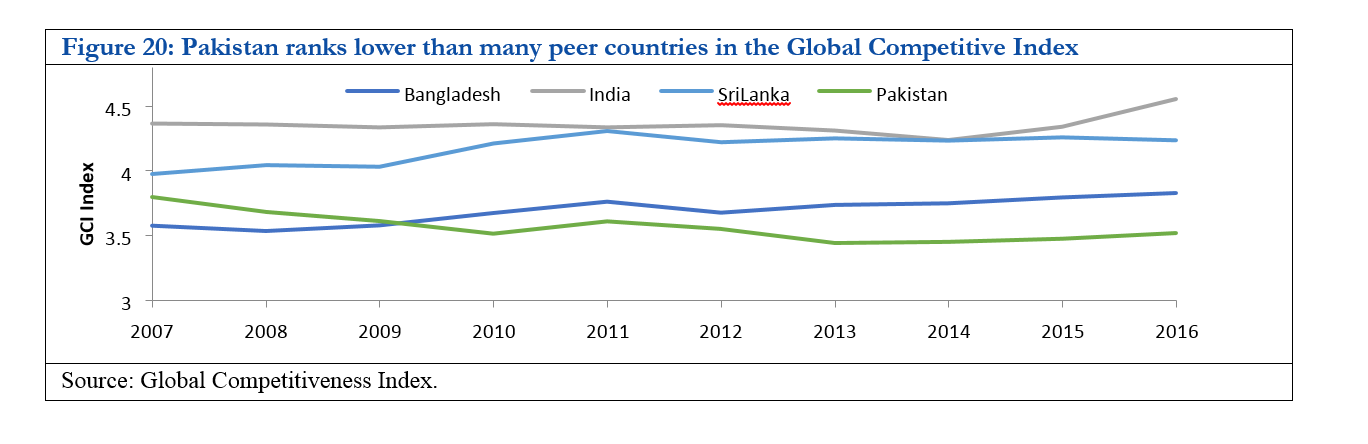

Pakistan ranks lower than many peer countries in the Global Competitive Index (GCI) ranking.The GCI tracks the performance of countries on 12 pillars of competitiveness. Pakistan is ranked markedly lower than India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh (Figure 20), particularly in pillars related to infrastructure, the macroeconomic environment, efficiency of goods and labor markets, and financial market development. With regards to technological readiness and business sophistication, there are slight improvements in the pillars for innovation, and higher education and training.

b. Weak Tax Administration

Complex tax administration and poor tax policy design undermine the business environment. Complex tax administration results in some sectors being very lightly taxed (e.g., the real estate sector), which can divert investments from more productive sectors to those with lower tax rates. Paying taxes is consistently identified by the private sector as a key constraint, not only because of the time it takes but also because of widespread perceived corruption at the federal and provincial revenue boards. Tax policies are often designed without taking into account potential adverse effects. A good example of this is the advance income tax through the withholding mechanism on financial transactions, which can be positive in terms of providing incentives for registering as a taxpayer but detrimental with regards to financial deepening by providing a disincentive to engage in the formal financial sector. Tax administration was complicated after the 18th Constitutional Amendment as the lack of coordination between provincial authorities in the case of cross-border supply of services has led to double taxation and a higher burden on businesses.

c. Lack of Entrepreneurship

Pakistan ranks poorly in the Global Entrepreneurship Index (GEI). A 2017 study conducted on the Global Entrepreneurship Index (GEI) ranks Pakistan 122 out of 137 countries, with an overall score of 15.2, significantly lower than peers such as India, China and Sri Lanka. This suggests a weak capacity of entrepreneurs in Pakistan, which is further constrained by limited human capital, technical know-how, staff training, and technology absorption.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To foster human and physical capital accumulation, a set of four interventions should be prioritized. First, to support human capital, programs to improve population management and allow families to take informed parenting decisions will be crucial. Lowering the fertility rate would have important feedback loops with other human development outcomes, female labor force participation and families’ ability to save and invest. Given Pakistan’s limited progress in this area, this should be a priority. Second, increased social spending will be necessary but, given Pakistan’s limited fiscal space, a first step would be to improve the efficiency of current spending. Third, a focus on early childhood development will be necessary to reduce malnutrition and stunting rates, which have life-long implications and affect the effectiveness of other human capital investments. Fourth, the priority to increase physical capital investments would be a far reaching domestic revenue mobilization effort. This would allow for increased public investment in crucial public areas that are currently underfunded, and it would also contribute to macroeconomic stability and reduce crowding out of the private sector from credit markets. This section provides an overview of the general direction these reforms could take. The Pakistan@100 policy notes ‘Growth and Investment’ and ‘Human Capital’ provide a more detailed discussion of the reforms necessary to allow Pakistan to reach upper middle-income status on its centenary.

i. Human Capital

Human development outcomes in Pakistan suggest the need to urgently increase investments and improve the effectiveness of services delivery so that the country can benefit from its large labor force. Despite progress, many human capital indicators remain weak and the outcomes have been stagnant or even declining in recent years, suggesting that investment has either been insufficient or ineffective in increasing human capital accumulation. Large disparities across provinces, between urban and rural areas, and by gender, among others, have persisted. The question thus arises as to what policies and institutions would best serve to improve the country’s human capital.

a. Ensure more and better public financing for human capital

Pakistan needs to significantly increase public spending in education, health and social protection. In 2017, Pakistan’s public expenditure on education and health was equal to 2.2 and 0.9 percent of GDP, respectively, noticeably below those of peer countries. This implies that Pakistan underinvests in human capital, leading to lower accumulation than in peer countries. In parallel with increased resources for human capital to levels similar to those in peer countries—5 percent of GDP for education and 2 percent of GDP for health—improvements in how these resources are spent will also be necessary. Given the limited fiscal space and that significantly increasing domestic revenues is a medium-term agenda, the government should first focus on increasing the efficiency of existing investments and prioritizing interventions for managing population growth and reducing stunting. As fiscal space opens and efficiency improvements are exhausted, the government should increase allocations to human capital investments.

b. Initiate awareness programs for family planning and parenthood

Develop comprehensive awareness programs to encourage informed decisions on parenthood. Due to a combination of cultural and social norms, discussions on reproductive health tend to be taboo and are not adequately discussed in the formal education system in Pakistan. This leaves many young people unprepared for the challenges and responsibilities of adult life with respect to responsible parenthood. Measures to increase informed parenthood should not merely include services and information for birth control, but also prepare young people for parenthood. Relevant knowledge, information and practices on reproductive health, young women’s health, and child development through health, nutrition and stimulation should be disseminated and learned through formal education, social campaigns and training, and health services.

c. Introduce targeted interventions for those lagging with an emphasis on women

The poor, who face challenges in meeting their immediate needs with limited resources, are often unable to utilize services due to various barriers. The government’s capabilities to deliver public services vary widely across regions, and so do the availability and quality of the services. Addressing these challenges requires a more robust service delivery system that helps all Pakistanis accumulate human capital. This will support poorer households to gain access to the services, while ensuring their availability and quality. This should be accompanied by targeted interventions (at both the federal and provincial levels) focusing on low-income populations and female empowerment. While the federal Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) provides basic support, in the context of decentralization there is a need to complement the federal-level efforts at the provincial level to empower women, reduce poverty, and provide resilience and opportunities for poor and vulnerable populations.

Investment in girls’ human capital cannot be overemphasized in targeted interventions. In Pakistan, too many girls drop out of school prematurely before they complete their secondary education. Not educating girls is especially costly because of the relationships between education, child marriage and early childbearing, and the risks that they entail for young mothers and their children.

d. Take a holistic approach for human capital investment focusing on the first 1,000 days

In implementing targeted intervention for human capital investment among the poor and vulnerable, the continuum of needs, especially during the first 1,000 days of the life cycle, should be noted. The WDR 2018 on learning suggests integrated programs for early years.

- Step 1. Family support package: Parental support including planning for family size, maternal education about health and nutrition, and children’s early nutrition and stimulation, as well as health, nutrition, and sanitation, particularly to vulnerable families.

- Step 2. Pregnancy package: Pre- and ante-natal care and information on nutrition.

- Step 3. Birth package: Attended and skilled delivery, birth registration, and exclusive breast feeding.

- Step 4. Child health and development package: Immunizations, information on deworming, identification and treatment of acute malnutrition, and other relevant information.

- Step 5. Pre-school package: Introduction of good quality pre-school and early childhood development programs.

- Step 6. Family life education: This module would need to be developed in an appropriate and locally sensitive manner to avoid any taboo issues. The introduction of respectful gender-based interactions in such education modules would be integral to improving women’s empowerment and agency for decision-making and labor force participation.

In the Pakistani context, it is worth adding an additional step regarding information-sharing, starting from the school level, about health and hygiene, nutrition and diet (within the local context, keeping in view the high poverty rates). These need to be introduced at every level of education

e. Skilling youth and the existing labor force to improve labor market opportunities

Equipping young people with the necessary human capital to participate in the labor market requires interventions in the primary, secondary and tertiary education levels. In addition to meeting targets in enrolment and completion rates, the government needs to focus on improving the quality of education. Possible pathways to achieve this include curriculum reform, teacher training and improved governance in the education sector. (For a detailed discussion on governance issues, refer to Chapter 5.) Investments in tertiary education should take the economy’s structure and potential into account. Accordingly, investments need to be made in establishing centers of excellence for research and applied sciences to support the priority sectors. Supporting the development of high quality higher-education institutes through proper regulation and regular monitoring is critical in curbing the emergence and growth of low-quality tertiary education institutions. There is a need to further develop student loan schemes that target students from lower-income quintiles and offer them equitable access to quality higher-education institutes (private or public).

While programs focusing on early education are critical for the future workforce, skills development and upgrading opportunities for the existing stock of the labor force who have missed out on the earlier opportunities for human capital are important. Even if the quality of the education system improves today and there is universal enrolment, these individuals will enter the labor force in at least 15 to 20 years’ time. Pakistan’s economy cannot wait that long. Policymakers need to focus on giving a second chance to the current stock of labor force to upgrade their skills, and find better and more productive jobs.

A suite of second-chance interventions for skills development for individuals of diverse needs and abilities can be considered. For instance, for the illiterate population, adult literacy and numeracy programs can be integrated with elements of financial literacy and socio-emotional skills training, which can help individuals in finding and retaining a job, or in starting a micro-enterprise. These programs could be targeted and customized to the specific needs of vulnerable groups, such as rural women from disadvantaged groups. Moreover, interventions to link workers to jobs through information provision and intermediation services should be considered, to improve employment outcomes.

ii. Physical Capital

Mobilize tax revenues to create adequate fiscal space for increasing public investments. Public investment is key for physical capital accumulation, both directly and because it can crowd in private sector investments. To increase public investment, Pakistan will need to increase tax revenues. Increasing it means that tax administration needs to be made taxpayer-friendly, technologically innovative and modern. A uniform tax code and administrative mechanism should be implemented, such that they support federalprovincial tax harmonization and integration. The establishment of a high-level constitutional body (e.g., a National Tax Council, such as the GST Council in India) through the Council of Common Interest, with clear accountability to resolve tax-related issues across the country, would facilitate these changes. Domestic revenue mobilization is a priority for Pakistan, because it will be crucial in avoiding the recurrent macroeconomic crises that affect the country, and because increased fiscal space will provide the resources needed to increase investments in priority areas such as health and education or infrastructure.

Improve the efficiency of public investment to crowd in private investment. Pakistan’s growth is lagging due to both low public and private investment. The fiscal space that will be created through increased revenue mobilization should be used to increase public investment, while also focusing on enhancing efficiency by improving project selection and management processes. Pakistan is currently embarked on a large infrastructure investment program, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). While CPEC holds great potential, it also entails challenges that highlight the need to improve public investment and fiscal risks management systems to better address emerging challenges.

Deepen financial intermediation to promote savings. Savings provide the basis for the financing of physical capital investment. Demographic changes that lower the high dependency ratio will be necessary to increase savings. A detailed discussion on reforms to reduce population growth can be found in the Pakistan@100 policy note on ‘Human Capital’. In parallel to these efforts, reforms in the financial sector can also incentivize increased savings. To meet the longer-term financing needs of the private sector, the development of a private corporate debt market is imperative. Efforts should also be made to diversify saving instruments offered by financial institutions, and to develop municipal and diaspora bonds to finance new projects.

Revive domestic investment activity by alleviating credit constraints. The key constraint to physical capital accumulation faced by SME entrepreneurs is the availability of credit. To reduce credit constraints, policies that encourage commercial banks to engage with SMEs should be implemented. This could, for example, include a continuation of financial reforms that strengthen creditor information systems and expand the pool of acceptable collateral (e.g., through a national collateral registry), or the establishment of specialized SME rating agencies. Policies that aim to improve banking features, such as expanding their operations to include electronic banking, might facilitate capital-deepening and improve access to finance. In addition, a prudent fiscal policy that limits government borrowing from the banking sector will avoid crowding out private sector borrowing.

Pakistan@100: Shaping the Future has been developed by the World Bank in partnership with Department for International Development (UK) and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia).