How Can a Growth Transformation Be Achieved?

A growth transformation requires a two-pronged strategy: on the one hand a focus on the reforms that will enable Pakistan to accumulate capital and allocate it more effectively, and on the other hand an overall improvement in governance that enables the implementation of a difficult set of reforms. Many reforms to increase investment and to support structural transformation have been attempted in the past, with mixed results. Reform implementation has often failed because of a weak governance environment that failed to provide the necessary political support for the implementation of difficult reforms. Improved governance will therefore be key in the form of increased transparency and accountability, a more effective institutional set-up and sufficient capacity. This report seeks to contribute to debates on both the reforms that will be necessary for a growth transformation and on the enabling governance environment.

Key Elements of a Growth Strategy

To trigger successful growth transitions, a country requires targeted policies that enhance the accumulation and allocation of human and physical capital, as well as sustainability. Reforms that improve accumulation, allocation, and sustainability jointly enhance a country’s factor endowments and productivity, and thus support sustainable and accelerated growth:

- Accumulation: Strong, enduring growth requires policies that encourage high rates of investment to accumulate human and physical capital, for example through investment in schools or infrastructure. China’s growth was driven primarily by factor accumulation, supported by policies to encourage household savings and public investments in infrastructure, and the education and health sectors.

- Allocation: Policies that aim to improve the allocation of physical capital and labor enhance productivity through structural transformation and opening the economy. For example, the Rep. of Korea in the 1960s reformed its economic policy toward an outward-oriented strategy, emphasizing trade and the promotion of commercialization of agriculture. This is widely credited with jump-starting growth, which was accompanied by a sharp reduction in the share of agriculture in GDP.

- Sustainability: Policies that target environmental and social sustainability ensure that high growth can be sustained over an extended period. This involves preventing growth that depletes the natural resource base. For instance, as part of its 11th Five-Year Plan, China has significantly increased investments in green sectors, especially energy efficiency and renewable energy, to reduce the country’s energy consumption and sustain growth in the long run. Sustaining growth is also about ensuring inclusive growth that allows all members of society to realize their economic potential. Malaysia’s “New Economic Policy” that coincided with the country’s growth acceleration emphasized equity and national unity, and has resulted in declining income and wealth inequality since the mid-1970s while maintaining high per capita GDP growth rates.

The right policies to accelerate and sustain growth differ widely across countries. Pakistan@100 is about identifying the policies that will work for Pakistan. To achieve upper middle-income status by its centenary, Pakistan must reverse its slowdown in investment and sustainably enhance its productivity. Pakistan@100 discusses options for Pakistan’s path toward achieving this long-term development vision, focusing on selected areas that matter for accelerating and sustaining growth, and identifying policies that target the key bottlenecks to growth. This report will thus provide detailed analysis to suggest the reforms and policies that are needed to increase human and physical capital, and enhance productivity through the more efficient allocation of capital and labor, while also contributing to social and environmental sustainability.

The focus areas in Pakistan@100 were selected after wide consultations with stakeholders at the inception phase, and corroborated by a thorough analysis of existing analysis and literature on growth in Pakistan. Any exercise that attempts to identify growth-enhancing reforms faces a trade-off between analytical depth and topical breadth. Pakistan@100 focuses on a limited number of issues to allow for a more detailed and in-depth analysis and discussion. To that end, seven policy notes were prepared, namely: (i) ‘Growth and Investment’; (ii) ‘Human Capital’; (iii) ‘Structural Transformation’; (iv) ‘Building a Case for Regional Connectivity’; (v) ‘Environmental Sustainability’; (vi) ‘From Poverty to Equity’; and (vii) ‘Governance and Institutions’. An additional note on gender, ‘Women’s Voice and Agency’, was also prepared to inform this work. These focus areas are in line with previous analytical work on growth in Pakistan:

- Increasing human and physical capital accumulation has been identified by the World Bank’s Country Economic Memorandum for Pakistan as a priority to support growth. Similarly, Qayyum et al. (2008) perform a growth diagnostic and highlight that returns to investment are low, which constrains investment rates.

- The need to enhance productivity through more efficient allocation of capital and labor, and improved regional connectivity is reflected in the Framework for Growth (2010), developed by the government of Pakistan, which focuses on the misallocation of resources resulting from policy distortions, limited competition, and barriers to entry, as well as a lack of openness to regional trade as impediments to growth. Similarly, Amjad and Burki (2015) highlight the need for greater regional connectivity and export-led growth in Pakistan, while the medium-term growth strategy developed for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (2015) focuses on regional trade and connectivity as emerging growth drivers, among others, for the province.

- Pakistan’s Vision 2025 (2014) emphasizes the importance of ensuring environmental sustainability and social equity, and is built on pillars that focus on inclusive growth. Similarly, the provincial growth strategies for Punjab (2015) and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (2015) both focus on inclusion and human capital development through investment in health and education.

Securing an Enabling Governance Environment

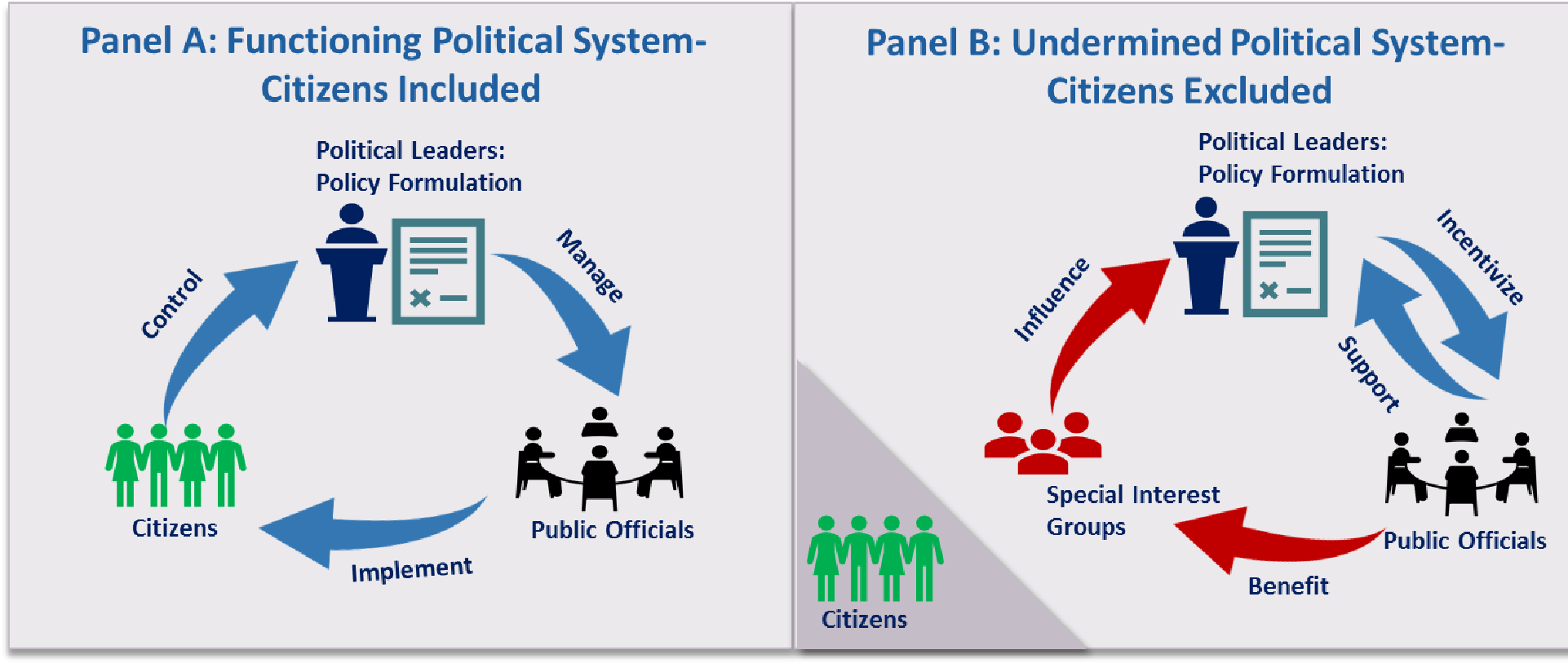

Transformational growth requires an enabling governance environment in which the incentives between political leaders, public officials and citizens are aligned. Good governance will be crucial in implementing the reforms needed to transform Pakistan. In a governance environment that is conducive to reform, citizens hold policymakers accountable to ensure that policies are consistent with their demands. Accountability requires that citizens can select political leaders who represent their interests, and sanction those who fail to deliver the public services and reforms citizens expect. Political leaders are, however, not only tasked with formulating policy, but also with managing and monitoring public officials to ensure the effective implementation of reforms. Thus, in a functioning political system, incentives are aligned toward providing public goods, as public officials target effective implementation to avoid being sanctioned by politicians, and political leaders represent citizens’ interests to remain in office. This can be presented as a triangular relationship between political leaders, public officials and citizens (Figure 5).

Capture by powerful elites and ‘clientelism’ means that the triangular relationship that defines a functioning political system fails, undermining a country’s ability to implement crucial reforms. Government failure occurs when leaders are selected based on their provision of private goods to select special interest groups, rather than their ability to provide public goods. Such situations can, for instance, arise when the high costs of running electoral campaigns require candidates to seek financial support from influential supporters and thus limit political competition. In such circumstances, candidates and politicians are responsive to interest groups and not to the public, which affects policy formulation and implementation. Such government failures can take many forms, but two are particularly prevalent. First, capture occurs when small groups can define policies according to their interest. Second, clientelism arises when political leaders exchange material goods for political support. In both cases, leaders have no political incentives to formulate and work toward the implementation of policies in the public interest.

There is a growing sentiment that Pakistan’s political economy is not conducive to reforms. Over the past decades, crucial reforms with seemingly broad support have nonetheless stalled. For example, reforms in the agriculture and water sectors, and to the tax and state-owned enterprise (SOE) systems, have been attempted but not successfully implemented:

- Agriculture: The government of Pakistan has traditionally intervened in agricultural input and output markets through subsidies and procurement prices. In the 1990s, the National Agricultural Policy was passed to reverse this practice and liberalize agricultural markets. However, reforms fell short of eliminating major sources of distortion, especially price floors for wheat, sugarcane and fertilizer subsidies, which continue to distort cropping choices, create entry barriers and constrain competition. Spielman et al. (2016) and Lieven (2011) argue that members of the landowning class have resisted the implementation of reforms, as they benefit from the status quo.

- Water: Pakistan uses 93 percent of its water resources for irrigation. Pricing for this water is subsidized and occurs on a flat-fee basis per acre of land, so that prices paid are not only low but also independent of the quantity of water used. Various reforms and agricultural strategies, including the National Water Policy (2003) and the government of Pakistan’s medium-term economic policy program for 2005-10 (MTDF 2005-10 [2005]), recommended introducing appropriate pricing mechanisms to achieve cost recovery and sustainability. Pakistan’s latest National Water Policy was only passed in 2018 and to date no major reform of the water-pricing system has been implemented. Large landowners both benefit disproportionately from the low water rates and have political connections that ensure their continued preferential access (Planning Commission, 2010).

- Tax Reform: Pakistan collects less than 13 percent of GDP in tax revenue, which is comparatively low. Including the agricultural sector in the tax net, which accounts for over 20 percent of GDP but had initially been excluded from taxation, is a potentially promising measure to increase revenue collection. However, although provinces passed legislation to collect agricultural income tax in FY97, actual collection remains insignificant—revenue from agriculture only accounts for 0.22 percent of total direct tax revenue—partially because full implementation would hurt politically connected landowning elites (Lieven, 2011; Nasim, 2012).

- State-Owned Enterprises: SOEs impose a significant fiscal cost. In FY2015/16, subsidies, loans and grants to federal SOEs accounted for 32.7 percent of the budget deficit and 1.5 percent of GDP. In the past three decades, the main policy to address this has been privatization, but several attempts have resulted in more limited divestments than targeted. Most recently, an over-ambitious privatization program launched in 2013 targeted more than 60 SOEs but only resulted in five transactions in the period 2013-15, and none thereafter. Despite successful privatization attempts in the telecommunications and financial sectors in the past, SOE reform has come to a standstill, as employment issues and vested interests oppose the necessary reforms.

Past reforms did not stall because Pakistan lacks implementation capacity. Pakistan has successfully undertaken difficult reforms in the past. For instance, the financial sector underwent reforms in the early 1990s that helped the country overcome the challenge of low performance and poor asset quality that had characterized the state-owned-bank-dominated sector. The reforms included the privatization of financial institutions, liberalization of interest rates, and a stop to credit controls and mandatory lending. Privatization and liberalization led to significant entry and diversification: the banking sector is now 85 percent privatelyowned and performing well, with relatively low non-performing loan (NPL) levels. Similarly, successful reforms were undertaken in the previously state-controlled media sector (Yusuf and Schoemaker, 2013). The sector’s liberalization in 2002 led to a dramatic increase in media outlets, from just three television channels in 2000 to 90 satellite television channels in 2017. This allowed the media to emerge as an important player in the country’s politics and gave marginalized parties the opportunity to communicate with the electorate, which improved political participation. The transformation of the National Database & Registration Authority (NADRA) from a manual thumbprint recording office to an innovative citizencentric ICT application and service provider is another successful example. NADRA is already helping the government administer smart card programs for disaster relief and financial inclusion schemes. The above suggests that with the necessary political will Pakistan does have the capacity to implement complex reforms (Dailami, 2015).

Reform efforts in Pakistan have often failed because they challenge an existing equilibrium of power. While most attempted economic reforms aim at supporting growth by enhancing economic efficiency, they also typically have redistributive effects. These occur by, for example, ensuring equal access to water resources, leveling the playing field in the agricultural sector, or collecting taxes to fund public services. By doing so, they adversely affect the interests of select groups that benefit from the status quo. These vested interests can work toward protecting their own benefits and preventing reforms (Kaplan, 2013; Husain, 2018), compromising the triangular relationship between citizens, policymakers and public officials that characterizes a functioning political system.

The capture of policy formulation occurs through two channels. First, groups that benefit from the status quo are politically connected and have established effective lobbies, which allows them to influence reforms for their own benefit. For example, Ahmad (2010) argues that the textile industry has worked against a reform of Pakistan’s Goods and Services Tax (GST) system to maintain a zero-rating of textile products. Similarly, the sugarcane lobby is politically connected and has influenced policy to maintain subsidies for the sector (PIDE, 2018). Second, beneficiary groups enter the political process directly, thus blurring the lines between political leaders and private interests. For example, the share of industrialists with a parliamentary mandate has doubled over the past 30 years (Daniyal and Bakhtian, 2012). There is also evidence that such direct political representation can be achieved by gathering support from voters in exchange for transfer payments. This has, for example, been documented for landowners who gather political support from their tenants, thus allowing them to compete for office and undermine reforms that reduce their access to agricultural rents (Beg, 2017)

In many instances, policy implementation has failed because public officials have entered clientelism relationship with political leaders. Such clientelism relationships are manifested in diverse areas such as health and education.

- Health: Absenteeism of doctors and health workers is linked to the political incentives of their supervisors: doctors are more likely to be absent in less-contested constituencies and in cases where their political supervisor is affiliated with the central party in power (Callen et al., 2014; Gulzar, 2014).

- Education: Public schoolteachers form a politically influential group in Pakistan, as their role in facilitating and administering elections makes them part of the political system (Andrabi et al., 2008). In addition, there is evidence that recruitment of public schoolteachers can be based on patronage rather than merit, with some teacher posts being ‘sold’ in exchange for cash or support (Hasnain, 2005). These political connections undermine political leaders’ authority to monitor and sanction teachers, which is manifested in worse performance of public school teachers than private schoolteachers, even though public schoolteachers are often better educated and better paid than private schoolteachers (Andrabi et al., 2008; Andrabi et al., 2017).

A lack of political competition has deprived voters of their ability to sanction political leaders for these failures. Even in the presence of elite capture and clientelism, voters can leverage the power of elections to voice their dissatisfaction with service delivery and reforms. However, there are constraints to this accountability mechanism. First, a lack of electoral competition, caused by the high costs of establishing party structures and mobilizing support, has given rise to dynastic politics, limiting voters’ ability to sanction political leaders (Cheema, Javid and Naseer, 2015). Second, an unfinished devolution agenda has thus far prevented potential gains to accountability from moving decision-making power over service delivery closer to the people. Thus, the examples discussed here and in the rest of the report, as well as research by some of Pakistan’s most reputed intellectuals, suggest that the triangular relationship linking citizens, policymakers and public officials is constrained in important ways.

The equilibrium of power currently in place in Pakistan does not only redistribute rents from the public to elites, but has profound impacts on growth, productivity and citizens’ welfare. The failure to implement effective reforms in select sectors affects growth by preventing factor accumulation and productivity growth. The poor track record of public schoolteachers means that one of Pakistan’s key assets—its young population—is accumulating less human capital than it could. Likewise, doctor absenteeism can lead to worse health outcomes, which directly impacts labor productivity. Examples of misallocation because of stalled reforms are equally manifold. For example, the absence of effective waterpricing mechanisms has led to an inefficient allocation of irrigation water across Pakistan, as downstream farmers receive less than one-third of the water than farmers at the head of canals (Rinaudo, 2008). At the same time, enormous quantities of water are wasted through irrigation, leading Pakistan to have one of the lowest levels of water efficiency in the world.

Pakistan@100 is about mapping out reforms to accelerate growth, but these cannot generate a growth dividend unless the political economy surrounding reforms is also addressed. Generating a governance environment that is conducive to reforms requires realigning the incentives of political leaders and public officials with citizens. Providing transparent and accessible information on the leaders’ trackrecords of reform and service delivery to citizens is a key step in this process. For example, providing report cards on children’s school performance has significantly improved learning outcomes in Pakistan, as it informs parents’ choice of school, and thus holds providers accountable (Andrabi et al., 2017).

Improving transparency alone is not sufficient, as citizens also need tools to hold their leaders accountable. Schooling report cards were effective in improving learning because the ability to choose between different private and public schools gives parents a lever to hold providers accountable. In circumstances where such levers do not exist, transparency is less successful. For example, providing public information on doctor absenteeism is ineffective in uncontested constituencies, i.e., in situations where citizens do not have a choice between political leaders, and who in turn have no incentive to hold service providers accountable (Callen et al., 2014). Thus, improving Pakistan’s political economy of reform requires increased transparency, and the provision of levers for citizens to sanction public officials and political leaders when policy and service delivery do not meet their expectations.

Increasing transparency and restarting efforts to devolve decision-making to the local level offer a promising pathway toward improving the political economy of service delivery. Fully implemented devolution would contribute to economic transformation and progress, as it allows local leaders to tailor service delivery to local needs and facilitates monitoring and sanctioning by voters based on service delivery performance. However, recently passed local government acts in Pakistan’s provinces have done little to devolve power to the local governments (with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa being an exception). This has undermined the full operation of local governments, depriving them of the authority to direct service delivery and assess local needs. Crucially, this has also undermined accountability, as it deprives voters of the ability to closely monitor the leaders responsible for providing public services. Reestablishing the chain of accountability by completing the devolution agenda, while increasing transparency and political competition, could be instrumental in increasing Pakistan’s prosperity on its centenary.